Numerous brain regions relevant to the pathophysiology of migraine, the cranial vascular system, the dura mater, and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord express estrogen receptors. This allows for the modulation of painful stimuli. Migraine attacks can occur in temporal relation to the menstrual window. Migraine is a risk factor for stroke and other vascular events. Extensive evidence exists that an increased risk of ischemic stroke is associated with both migraine without aura and migraine with aura. Since the risk of stroke may also be increased with the use of hormonal contraceptives, the question of practical management options is significant.

Classification of migraine in relation to menstruation

The current 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD3) [1], like previous editions, does not include a section for migraine attacks that occur in relation to the menstrual window in the main body of the classification. The first edition in 1988 [2] did not provide any formal criteria for menstrual-related migraine. However, even in this first edition, the commentary noted that some women experience migraine attacks without aura exclusively during menstruation. This was termed "menstrual migraine." The term was to be used only if at least 90% of the attacks occurred in the period from two days before menstruation to the last day of menstruation. In the second edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders in 2004 [3], two subtypes of menstrual-related migraine were defined for the first time in the appendix. The so-called "pure menstrual migraine" refers to attacks that occur exclusively in connection with menstruation. In contrast, so-called "menstrual-associated migraine" is characterized by attacks occurring at other times during the menstrual cycle. Both forms are subgroups of migraine without aura. The appendix to the International Classification of Headache Disorders describes research criteria for headache entities that have not yet been sufficiently validated by scientific studies. Both the experience of the members of the Headache Classification Committee and publications of varying quality suggest the existence of these entities listed in the appendix, which can be considered distinct diseases. However, further scientific evidence is required before they can be formally accepted. If this is achieved, these diagnoses from the appendix can be incorporated into the main body of the classification in the next revision.

Even in the 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICD) from 2018, "pure menstrual migraine" and "menstrual-associated migraine" are still only found in the appendix. For both diagnoses, it is required that migraine attacks occur on day 1 ± 2 of menstruation (i.e., day −2 to +3) in at least 2 out of 3 menstrual cycles (Table 1, Fig. 1). However, the criteria have now been expanded to include a subtype with aura, although menstrual migraine attacks usually occur without aura. Thus, pure menstrual migraine with and without aura, as well as menstrual-associated migraine with and without aura, are defined. When pure menstrual migraine and menstrual-associated migraine are combined, the term "menstrual migraine" is used as a general term [4].

Table 1. ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria for migraine within and outside the menstrual window

———————————————————————————

A1.1.1 Purely menstrual migraine without aura

- Attacks in a menstruating woman 1 , which meet migraine without aura

- The attacks occur exclusively on day 1 ± 2 (i.e., day −2 to +3) of menstruation 1 in at least 2 out of 3 menstrual cycles and at no other time of the cycle.

A1.1.2 Menstrual-associated migraine without aura

- Attacks in a menstruating woman that meet the criteria for 1.1 migraine without aura as well as criterion B below

- The attacks occur on day 1 ± 2 of menstruation ( i.e. day −2 to +3) in at least 2 out of 3 menstrual cycles, but also at other times of the cycle.

A1.1.3 Non-menstrual migraine without aura

- Attacks in a menstruating woman that meet the criteria of 1.1 migraine without aura as well as criterion B below.

- meet criterion B for A1.1.1 purely menstrual migraine without aura or A1.1.2 menstruation-associated migraine without aura

———————————————————————————

A1.2.0.1 Purely menstrual migraine with aura

- Attacks in a menstruating woman 1 , which meet the criteria of 1.2 migraine with aura and criterion B below

- The attacks occur on day 1 ± 2 of menstruation (i.e., day −2 to +3) in at least 2 out of 3 menstrual cycles, but also at other times of the cycle.

A1.2.0.2 Menstrual-associated migraine with aura

- Attacks in a menstruating woman that meet the criteria for 1.2 migraine with aura and criterion B below

- The attacks occur on day 1 ± 2 of menstruation ( i.e. day −2 to +3) in at least 2 out of 3 menstrual cycles, but also at other times of the cycle.

A1.2.0.3 Non-menstrual migraine with aura

- Attacks in a menstruating woman that meet the criteria for 1.2 migraine with aura and criterion B below

- meet criterion B for A1.2.0.1 purely menstrual migraine with aura or A1.2.0.2 menstruation-associated migraine with aura

———————————————————————————

For the purposes of ICHD-3, menstruation is considered endometrial bleeding resulting from the normal endogenous menstrual cycle or withdrawal from external progestogens, the latter being the case for combined oral contraceptives and cyclic hormone replacement therapy (Fig. 1). The distinction between purely menstrual migraine without aura and menstruation-associated migraine without aura is important according to ICHD-3 because hormone prophylaxis is more likely to be effective in the latter [1].

More than 50% of women with migraine report an association between menstruation and migraine [5]. The prevalence varies across studies due to differing diagnostic criteria. The prevalence of menstrual migraine without aura ranges from 7% to 14% in migraine patients, while the prevalence of menstrual migraine without aura ranges from 10% to 71% in migraine patients. Approximately one in three to five migraine patients experiences a migraine attack without aura in connection with menstruation [5]. Many women tend to overestimate the association between menstruation and migraine attacks; for research purposes, the diagnosis requires prospectively documented evidence of a minimum of three cycles, supported by a migraine app or diary entries [1].

The mechanisms of migraine may differ depending on whether the endometrial bleeding occurs as a consequence of the normal endogenous menstrual cycle or of withdrawal from external progestogens (as with combined oral contraceptives and cyclic hormone replacement therapy). The endogenous menstrual cycle results from complex hormonal changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis that trigger ovulation, which is suppressed by the use of combined oral contraceptives. These subpopulations should therefore be considered pathophysiologically separately, even though the diagnostic criteria are not mutually distinguishable.

There is evidence that, at least in some women, menstrual migraine attacks may be triggered by estrogen withdrawal, although other hormonal or biochemical changes at this point in the cycle may also be relevant [4]. If purely menstrual migraine or menstruation-associated migraine is associated with exogenous estrogen withdrawal, both diagnoses should be given: purely menstrual migraine without aura or menstruation-associated migraine without aura and estrogen withdrawal headache. The association with menstruation may change over the course of a woman's reproductive life.

Effect of hormones on headaches

The effect of hormones on headaches was included in the main section "secondary headaches" in the 2nd edition 2004 (ICHD-2) of the International Classification of Headache Disorders [3]. The criteria concern headaches that have newly developed in connection with hormone administration or pre-existing headaches that worsen as a result. The criteria require that the headaches improve after discontinuation of the hormones or, in the case of pre-existing headaches, that the previous pattern reappears.

The 3rd edition of the ICHD-3 (2018) [1] required the presence of headaches on at least 15 days per month for a diagnosis of exogenous hormone-related headache. The ICHD-3 diagnosis of estrogen withdrawal headache requires that headaches begin within 5 days of discontinuing estrogen if women have taken estrogens for at least three weeks.

Estrogens and migraines

In 1972, Somerville described how intramuscular injection of estradiol valerate, a prodrug ester of 17β-estradiol, shortly before menstruation could delay the onset of a menstrual-associated migraine attack [6]. A threshold concentration of circulating 17β-estradiol of 45–50 pg/ml was identified below which a migraine attack can be triggered. This threshold was also observed in postmenopausal women undergoing hormone replacement therapy with intramuscular 17β-estradiol. Based on these data, the hypothesis was put forward that migraine attacks during the menstrual window are triggered by a drop in estrogen. It was further postulated that physiological estrogen fluctuations play a role in migraine pathogenesis. This assumption was supported by the finding that there is a particular susceptibility to migraine attacks during the estrogen decline in the late luteal phase. However, no differences in the maximum or mean daily estrogen concentrations during ovulation cycles could be demonstrated in migraine patients compared to healthy controls [4, 7].

Estrogen and nervous system

The most relevant endogenous estrogen is 17β-estradiol [8]. It enters the central nervous system via passive diffusion across the blood-brain barrier. However, it can also be synthesized locally in the brain from cholesterol or from aromatized precursors by the enzyme aromatase and act there as a neurosteroid. The physiological effects can be mediated by activation of various estrogen receptors, in particular estrogen receptor-α (ERα), estrogen receptor-β (ERβ), and G protein-coupled estrogen receptor-1 (GPER/GPR30) [9].

Estrogens exert their biological effects in the central nervous system through genomic or non-genomic cellular mechanisms. This can alter neurotransmission and cell function. Intracellular signaling cascades can modify enzymatic reactions, ion channel conductance, and neuronal excitability [4].

Numerous brain regions involved in the pathophysiology of migraine express estrogen receptors. This is particularly true for the hypothalamus, cerebellum, limbic system, pontine nuclei, and periaqueductal gray (substantia grisea periaquaeductalis). Estrogen receptors are also expressed in the cerebral cortex, thereby modulating pain sensitivity both afferently and efferently. The cranial vascular system, dura mater, and dorsal horn of the spinal cord also express estrogen receptors, thus modulating painful stimuli [4, 8, 9].

Genome-wide association studies have shown no correlation between estrogen receptor polymorphisms and an increased risk of migraine. However, a single nucleoid polymorphism in the SYNE1 gene has been identified in association with menstrual migraine [10].

The serotonergic system can be activated by estrogen, which may have a protective effect against migraine attacks [11]. Estrogen can also increase the excitatory effect of glutamate. This may explain the increased likelihood of developing a migraine aura during periods of high estrogen concentrations, such as during pregnancy or when taking exogenous hormones.

Estrogen can modulate the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system, which has an inhibitory effect in the nervous system [12]. Progesterone, which is mainly produced by the corpus luteum of the ovaries, as well as its metabolite allopregnanolone, can enhance GABAergic activity and thus exert an antinociceptive effect.

Estrogens can also modulate the endogenous opioid system by increasing the synthesis of enkephalin [13]. Accordingly, decreased estrogen and progesterone levels during the late luteal phase may correlate with reduced activation of the opioid system. This leads to increased pain sensitivity. Studies on pain sensitivity during the different phases of the menstrual cycle have shown increased sensitivity during the luteal phase, particularly in women who experience premenstrual symptoms [14]. High estrogen concentrations also promote the production of other pain-inhibiting neurotransmitters and neuropeptides, such as neuropeptide Y, prolactin, and vasopressin, which may play a role in the development of migraine [4].

Oxytocin and migraine

The neuropeptide oxytocin is produced in the hypothalamus. It has extensive effects on the central nervous system. In particular, it modulates mood and behavior. It influences the body's own pain control and can have a migraine-preventive effect [4]. During periods of elevated estrogen concentrations, oxytocin levels are also increased. Estrogen leads to increased production of oxytocin in the hypothalamus and other brain regions, especially in the caudal trigeminal nucleus [15]. Women suffering from menstrual migraine show lowered pain thresholds during the hormone-free phase when taking combined hormonal contraceptives, i.e., at the time of reduced estrogen concentrations [16].

The pathophysiology of migraine is associated with increased cortical nociceptive activity in the trigeminal-vascular nociceptive system. This leads to both vasodilation of intracranial vessels and meningeal inflammation [15]. Local activation of estrogen receptors in the trigeminal ganglion may trigger migraine attacks. Women have more estrogen receptors in the trigeminal ganglion than men [17]. Estrogens can acutely influence vascular tone by inhibiting calcium channels in smooth muscle [18]. Estrogens can also activate cortical spreading depression (CSD), a cortical neuronal depolarization that is considered a characteristic feature of migraine with aura [19]. High estrogen levels increase susceptibility to CSD, while estrogen deprivation reduces it. This could explain why migraine attacks during the menstrual window are less frequently associated with an aura [1].

Estrogens and calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRP)

The release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is now considered a crucial step in the pathophysiology of migraine. Stimulation of the trigeminal ganglion can lead to the release of CGRP and substance P into the cranial bloodstream [20]. CGRP activates nociceptive mechanisms in the dura mater, the trigeminal ganglion, the cervical trigeminal nucleus complex, the thalamus, and the periaquaductal gray, among other locations [20]. Both the clinical symptoms of migraine and the release of CGRP can be blocked by triptans [21]. CGRP infusions can provoke an attack in migraine patients [22]. This is not the case in healthy controls. Monoclonal antibodies specifically targeting CGRP as a ligand (eptinezumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab) or the CGRP receptor (erenumab) are now available for the preventive treatment of episodic and chronic migraine [23, 24]. They have been shown to be effective and well-tolerated in controlled trials.

CGRP levels are higher in women than in men [25]. They are also elevated during pregnancy and with the use of combined hormonal contraceptives. During menopause, levels are variable [26]. CGRP and estrogen receptors are expressed in the same brain regions. Estrogen can modulate CGRP production in trigeminal neurons. Experimentally, administration of exogenous estrogen leads to reduced CGRP levels [27]. During postmenopause, CGRP levels may be elevated while estrogen concentrations are reduced [28].

Substance P, a vasoactive neuropeptide, can also cause neurogenic inflammation in the meninges associated with migraine [28]. Estrogen administration can reduce plasma levels of substance P. In summary, estrogen can modulate both CGRP and substance P through inhibitory effects. Estrogen thus provides a protective mechanism against neurogenic inflammation [28]. Furthermore, estrogen can inhibit the activating effect of progesterone on CGRP and substance P. This suggests that the combination of estrogen and progesterone has a stabilizing effect on CGRP and substance P release [4].

Migraine patients exhibit elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokinins both during and between migraine attacks [29]. Experimental studies suggest that estrogens can inhibit circulating inflammatory molecules. Additionally, they have a protective effect against prostaglandin-induced inflammation. Conversely, estrogen deprivation can increase sensitivity to prostaglandins and activate neuroinflammation by increasing the release of neuropeptides such as CGRP, substance P, and neurokinin [30].

In summary, the available data indicate that estrogen does not exert a direct protective effect on migraine attacks. However, estrogen can indirectly influence activating and inhibitory migraine factors. Consequently, the initiation of migraine attacks in the neurovascular system may be inhibited. In the trigeminal circulation, sensitivity to migraine may be reduced. Reduced estrogen concentrations can lower the threshold for migraine attacks [4, 15].

Estrogens in the prevention of menstrual migraines

In some patients, migraine attacks may occur exclusively during the menstrual window [1]. These attacks may exhibit significantly more severe pain characteristics (duration, intensity, aggravation by physical activity) and accompanying symptoms (nausea, vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia) compared to migraine attacks outside the menstrual window.

Manipulating natural estrogen concentrations may be a way to prevent menstrual-associated migraine attacks. The aim is to reduce hormonal fluctuations and the drop in estrogen levels during menstruation. This is based on the observation that susceptibility to migraine attacks during the perimenstrual window (days -2 and +3 of menstruation) correlates with the drop in hormone levels [31].

Basically, there are two approaches available for using hormones in the preventive treatment of menstrual migraine:

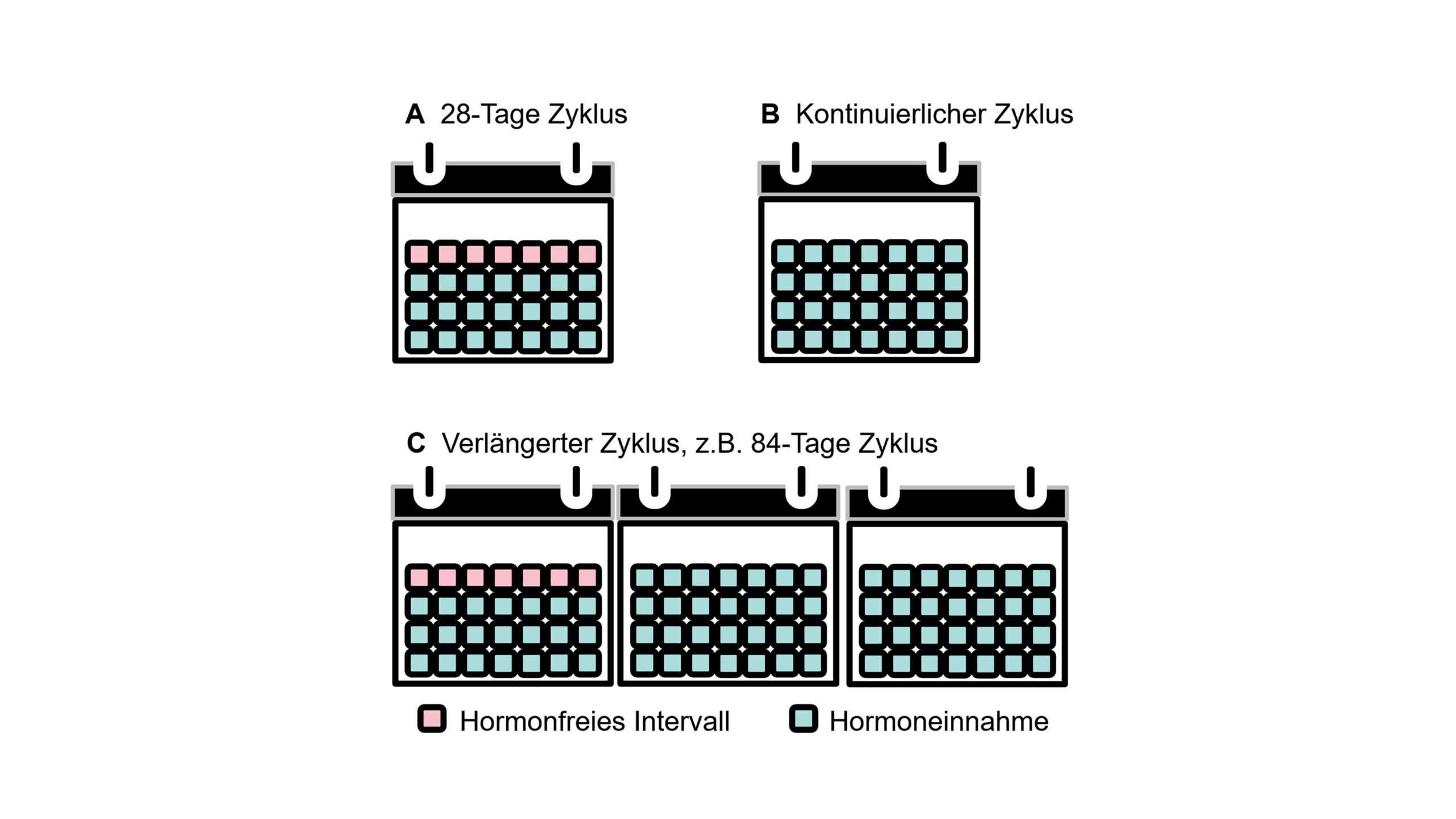

- Hormonal contraceptives can be used with different ethinylestradiol administration regimens, depending on the duration of the hormone-free interval. These regimens include the standard 21/7 regimen, variable extended regimens, and continuous regimens without hormone-free intervals (Fig. 2). Administration options include oral hormonal contraceptives and vaginal rings.

- Furthermore, estrogen supplements not intended for contraception can also be used. Examples include transdermal patches, gel applications, and subcutaneous implants. These aim to compensate for the drop in estrogen levels during the perimenstrual period in cases of menstrual migraine and pure menstrual migraine.

The data on the use of hormones in the prevention of menstrual migraine are very limited and partly contradictory. The rationale is to compensate for the drop in endogenous estrogen in patients with pure menstrual migraine who have predictable menstruation [4, 32, 33]. On the other hand, continuous administration of low doses is intended to counteract physiological hormone fluctuations. The combined administration of estrogen and progestins is intended to stabilize hormone levels and enable contraception [4, 32, 33]. Various options for influencing the female hormonal cycle for the treatment of migraine are described below.

Desogestrel (progestin-only drug)

Four open-label observational studies investigated the effect of desogestrel 75 µg per day in women with migraine with and without aura [34-37]. The women studied were taking the drug either for contraception or for medical reasons – but not for targeted migraine prophylaxis. Side effects of desogestrel included worsening headaches, prolonged bleeding time, spotting, and acne. In contrast, there is only limited evidence for the efficacy of desogestrel on the course of migraine in women with migraine without aura or migraine with aura. Given its favorable cardiovascular risk profile, desogestrel may be considered in women with migraine with or without aura and additional vascular risk factors.

Combined oral contraceptives

Current research on the extended use of combined oral contraceptives in women with migraine is limited [4, 32]. Here, too, only open-label observational studies are available, conducted in women who took the drug for contraception or for medical reasons – not for migraine prophylaxis. Only one study specifically used combined oral contraceptives for headache prevention [38]. The available data suggest a potential benefit of long-term use of combined hormonal contraceptives in women with migraine without aura.

Desogestrel versus extended use of combined oral contraceptives

Open-label observational studies have compared the effect of the desogestrel mini-pill with extended use of combined oral contraceptives in migraine without aura. A study by Morotti et al. [36] found no difference in the number of migraine days, headache days, headache intensity, or days used with triptans. Current studies comparing the desogestrel mini-pill with combined oral contraceptives are limited. The results of observational studies do not allow for definitive conclusions regarding efficacy.

Combined oral contraceptives with a shortened pill-free interval

For the use of combined oral contraceptives with a shortened pill-free interval, only studies of low quality are available [4, 32]. These studies exhibit highly heterogeneous regimens. There is no evidence for the superiority of any specific regimen compared to other options. Sufficient evidence is lacking to justify using this treatment solely for migraine prevention. In some women, the treatment had to be discontinued prematurely due to a worsening of their migraine.

Combined oral contraceptives with oral estrogen administration during the "pill-free period"

Evidence for the use of oral combined hormonal contraceptives with oral estrogen replacement during the pill-free interval is available from only one study [39]. Current data do not allow for any conclusions regarding the efficacy of this treatment regimen on the course of migraine.

Combined oral contraceptives with estradiol supplementation via a patch during the pill-free period

In a single-center study, no significant reduction in the number of migraine days, migraine severity, or migraine symptoms was observed [40]. Adverse events associated with transdermal estradiol supplementation included altered withdrawal bleeding. Current data do not provide sufficient justification for the use of estradiol patches for migraine prevention during the pill-free interval.

Combined hormonal contraceptive patches

The data on the use of combined hormonal contraceptive patches are very limited. Data are available from only one study [41]. The results of this study suggest a link between hormone withdrawal and the occurrence of headaches. The number of headache days was higher during the week without the patch. After removal of the patch following prolonged treatment, the frequency of headaches did not increase. The current body of research does not provide evidence for the use of this approach.

Combined hormonal vaginal ring for contraception

The use of combined hormonal contraception with a vaginal ring on the course of migraine is also very limited [42]. The available data are insufficient to justify its use for migraine prevention [4, 32].

Transdermal estradiol supplementation with gel

The effect of transdermal estradiol gel supplementation in premenopausal patients was investigated in three studies [43-45]. Estradiol gel 1.5 mg was administered for 6 or 7 days. The effect was compared to placebo. Treatment in these studies was specifically for headache prevention. No serious adverse events associated with the use of estradiol gel were reported. Rash, anxiety, or amenorrhea were documented as adverse effects. Based on the current evidence, the use of transdermal estradiol gel for migraine prevention is not sufficiently justified. On the one hand, the administration of transdermal estradiol gel is simple and generally well tolerated. On the other hand, the timing of application can be problematic in cases of irregular menstruation. The potential increase in migraine symptoms due to delayed estrogen withdrawal can also be a disadvantage. This can be caused by increased estradiol administration with additional estradiol supplementation and a more pronounced decline. The follicular rise of endogenous estrogen can also be inhibited by exogenous administration. Due to a lack of data, the administration of estrogen gel cannot currently be recommended for the prevention of menstrual migraine. This approach can currently be considered only if all other strategies are insufficiently effective in preventing menstrual migraine.

Transdermal estradiol supplementation via a patch

The evidence for the use of transdermal estradiol patch supplementation for the treatment of menstrual migraine is limited. The rationale for its use is to maintain stable estradiol concentrations before the onset of menstruation [41]. Currently, there are no data demonstrating the efficacy of estradiol patch supplementation on the course of migraine.

Transdermal estrogen supplementation with patches in women with pharmacologically induced menopause

The use of transdermal estradiol patches in women with pharmacologically induced menopause is not sufficiently justified based on current data. During pharmacologically induced menopause, the risk of osteoporosis, depression, hot flashes, irritability, decreased libido, and vaginal dryness is increased. This risk can be reduced by estrogen supplementation therapy [46]. Current evidence is insufficient to support its use for migraine prophylaxis.

Subcutaneous estrogen implant with cyclic progestogen

An open-label observational study investigated the use of a subcutaneous estrogen implant with cyclic progestogen [47]. The available data do not allow for sufficient conclusions regarding its potential use in migraine prevention.

Add-back therapy

The course of headaches was investigated in women receiving a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue, a trigger of transient iatrogenic menopause, plus a transdermal estrogen patch, alone or in combination with a progestogen (add-back therapy) [48]. A reduction in headache severity was observed, but not in headache frequency. This study suggests that reducing hormonal fluctuations could be beneficial in preventing out-of-menstrual migraine.

Phytoestrogens

Phytoestrogens are secondary plant compounds such as isoflavones and lignans. They are not estrogens in the chemical sense, but they share structural similarities. This results in a weak estrogenic or antiestrogenic effect. The best-known phytoestrogens are the isoflavones genistein, daidzein, and coumestrol. Genistein and daidzein, in particular, are used to relieve hot flashes and other menopausal symptoms, as well as menstrual migraine. In an open-label study over 10 days during the menstrual cycle (from -7 to +3 days), a mean reduction of headache days of 62% was observed [49]. Half of the patients reported an absence of nausea and vomiting associated with migraine. A randomized controlled trial confirmed this effect over 24 weeks with a treatment regimen of 60 mg soy isoflavones, 100 mg dong quai, and 50 mg black cohosh [50]. This study showed a highly significant reduction in menstrual migraine, the use of acute medication, and headache severity. Phytoestrogens could therefore potentially be an option for women who do not want to take hormone treatments or cannot use them due to contraindications, such as a significant cardiovascular risk profile.

Further hormone treatments

Studies on the use of contraceptive options for headache prevention have shown that inducing amenorrhea is associated with a significant reduction in headaches [4, 32]. Progesterone-only therapies have a lower risk of cardiovascular events or complications than estrogens [4, 30, 33]. These can also be effective in preventing migraine with aura. Due to continuous administration, cycle-related fluctuations in female sex hormones and acute estrogen withdrawal do not occur.

Testosterone has been shown to suppress cortical spreading depression in preclinical studies [51]. Subcutaneous administration of testosterone implants can reduce the severity of headaches in patients with androgen insufficiency. Following oophorectomy with androgen insufficiency, women report an increase in migraine frequency compared to women who enter natural menopause [52].

Women undergoing hormone replacement therapy (HRT) during menopause often experience a worsening of their headaches [53]. This is likely due to irregular estrogen release. HRT may help stabilize estrogen withdrawal in this situation. The lowest effective dose should be used to control menopausal symptoms and avoid cardiovascular side effects, particularly in migraine with aura. Transdermal estrogen administration or the use of continuous combined regimens, such as HRT, which avoid bleeding, may be the best approach to prevent migraine in this situation.

Topiramate, menstrual migraine and contraception

Topiramate is approved for the preventive treatment of migraine and is also used for menstrual migraine. When using topiramate daily doses above 200 mg, the possibility of reduced contraceptive efficacy and increased breakthrough bleeding should be considered in patients using combined oral contraceptives [54]. Women using estrogen-containing contraceptives should be advised to inform their healthcare provider of any changes in their menstrual bleeding. Contraceptive efficacy may be reduced by topiramate treatment even in the absence of breakthrough bleeding [55].

CGRP-mAK and menstrual migraine

Currently, there is no specific preventive treatment for menstrual migraine. Recently, the use of monoclonal antibodies against CGRP or the CGRP receptor for the treatment of menstrual migraine has been investigated. Due to their long half-life, these have the advantage that, particularly in long-term treatment, they only need to be administered monthly or every three months. Galcanezumab, erenumab, eptinezumab, and fremanezumab are now available in Germany for the preventive treatment of migraine. In a study with erenumab [56], the course of menstrual migraine was compared between a group that responded to erenumab and a group that did not. The results showed that in both groups, the frequency of headaches was higher within the menstrual window than outside of it. This means that even with treatment with erenumab, migraine occurs more frequently during the menstrual window than outside of it. In another study, the efficacy of erenumab in preventing menstrual migraine was analyzed [57]. The monthly migraine days included both perimenstrual and intermenstrual migraine attacks. Erenumab 70 mg and 140 mg significantly reduced the frequency of migraine days per month compared to placebo. The data demonstrate the efficacy of erenumab in preventing menstrual migraine [57].

Cardiovascular risk

Migraine patients have approximately twice the risk of stroke compared to healthy controls. This is especially true for migraine with aura. Migraine is a risk factor for stroke as significant as thrombophilia, patent foramen ovale, arterial dissection, smoking, and obesity [4, 30, 32, 33, 58-60].

Estrogens improve endothelial-dependent blood flow and lipid profiles. However, they also have prothrombotic and pro-inflammatory effects. These can be particularly relevant in patients at increased risk of stroke and other vascular events such as myocardial infarction or deep vein thrombosis. The use of combined oral contraceptives may be associated with an earlier onset of stroke [4, 32, 61, 62].

In principle, the presence of two independent risk factors for stroke must be carefully weighed. Studies show that women with migraine who also use combined hormonal contraceptives have an increased risk of stroke of 2.1–13.9 [33, 61]. The risk of stroke correlates with the estrogen dose. Expert guidelines from the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESCRH) [32, 33], the German Society of Neurology (DGN) in collaboration with the German Migraine and Headache Society [63], and the German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics [62] therefore do not recommend the use of combined hormonal contraceptives for patients with migraine with aura. Patients with migraine without aura should not use combined hormonal contraceptives if other vascular risk factors are present. Alternatively, contraceptives containing only progestogen or combined oral contraceptives with estrogen doses lower than 35 µg can be considered.

To prevent menstrual migraine, extended cycle regimens and treatments with stable hormone levels, such as transvaginal administration or transdermal estradiol supplementation, can be used. Low doses of estrogen can also be considered for these patients. However, the current data are still insufficient to make reliable statements about efficacy and tolerability. Even though progestin monotherapy has the safest vascular risk profile, side effects such as breakthrough bleeding can still occur.

Overall, the studies show that estrogen therapy is the most effective and well-tolerated treatment. Future studies on the efficacy and tolerability of natural estrogen will also be important. A short hormone-free interval is likely the most effective way to prevent a drop in estrogen levels that could potentially trigger a migraine attack. However, further controlled studies are needed to make reliable conclusions in this area.

Current guideline recommendations for the prophylaxis of menstrual migraines

The current guideline of the German Society for Neurology (DGN) in collaboration with the German Migraine and Headache Society [63] from 2022 recommends the long-acting NSAID naproxen (half-life 12–15 h) or a triptan with a long half-life for short-term prophylaxis of menstrual migraine. The drugs should be administered for 5–6 days, starting 2 days before the expected onset of menstruation. Furthermore, the continuous administration of a combined oral contraceptive can be considered as a preventive measure. The administration of desogestrel can also be considered for the prophylaxis of menstrual migraine.

Placebo-controlled studies exist for the use of frovatriptan 2.5 mg once, twice, or three times daily, zolmitriptan 2.5 mg twice or three times daily, naratriptan 1 mg or 2.5 mg twice daily, and naproxen 550 mg twice daily. Administration should begin two days before the expected onset of a migraine attack during the menstrual window and continue for a total of 6–7 days. The risk of developing medication-overuse headache when using naproxen or a triptan for short-term prophylaxis of menstrual migraine is considered low, provided that few other acute medications are used.

Current guidelines do not recommend percutaneous estrogen administration. This is due to a delayed onset of migraine attacks after discontinuation of the estrogen gel. Percutaneous estrogen supplementation should only be considered if other preventive measures are ineffective. A prerequisite for this approach is a regular menstrual cycle to determine the optimal timing of application. Additional percutaneous estrogen supplementation during the pill-free interval is not recommended for the prophylaxis of menstrual migraine due to a lack of data.

According to current guidelines, the continuous use of a combined oral contraceptive can be considered as a preventive measure. The aim is to reduce the number of cycles and the migraine attacks they trigger. Continuous use for up to two years is considered safe. The guidelines point out that this preventive treatment for headaches and migraine attacks outside the menstrual window has so far only been investigated in open-label, uncontrolled studies. Since combined oral contraceptives can significantly increase the risk of stroke, and migraine with aura is itself a risk factor for stroke, the individual cardiovascular risk profile of each patient must be taken into account. According to the guidelines, the continuous use of combined oral contraceptives is least problematic in patients with migraine without aura and without other cardiovascular risk factors. Otherwise, the indication must be strictly defined, patients must be adequately informed, and the procedure must be decided on a case-by-case basis. Combined oral contraceptives with a low estrogen content should generally be preferred. A contraindication for the administration of combined oral contraceptives is highly active migraine with aura in patients with an elevated vascular risk profile.

Adequate contraception must also be ensured during various preventive migraine therapies. This applies particularly to treatment with monoclonal antibodies against CGRP or the CGRP receptor, botulinum toxin, flunarizine, topiramate, and valproate.

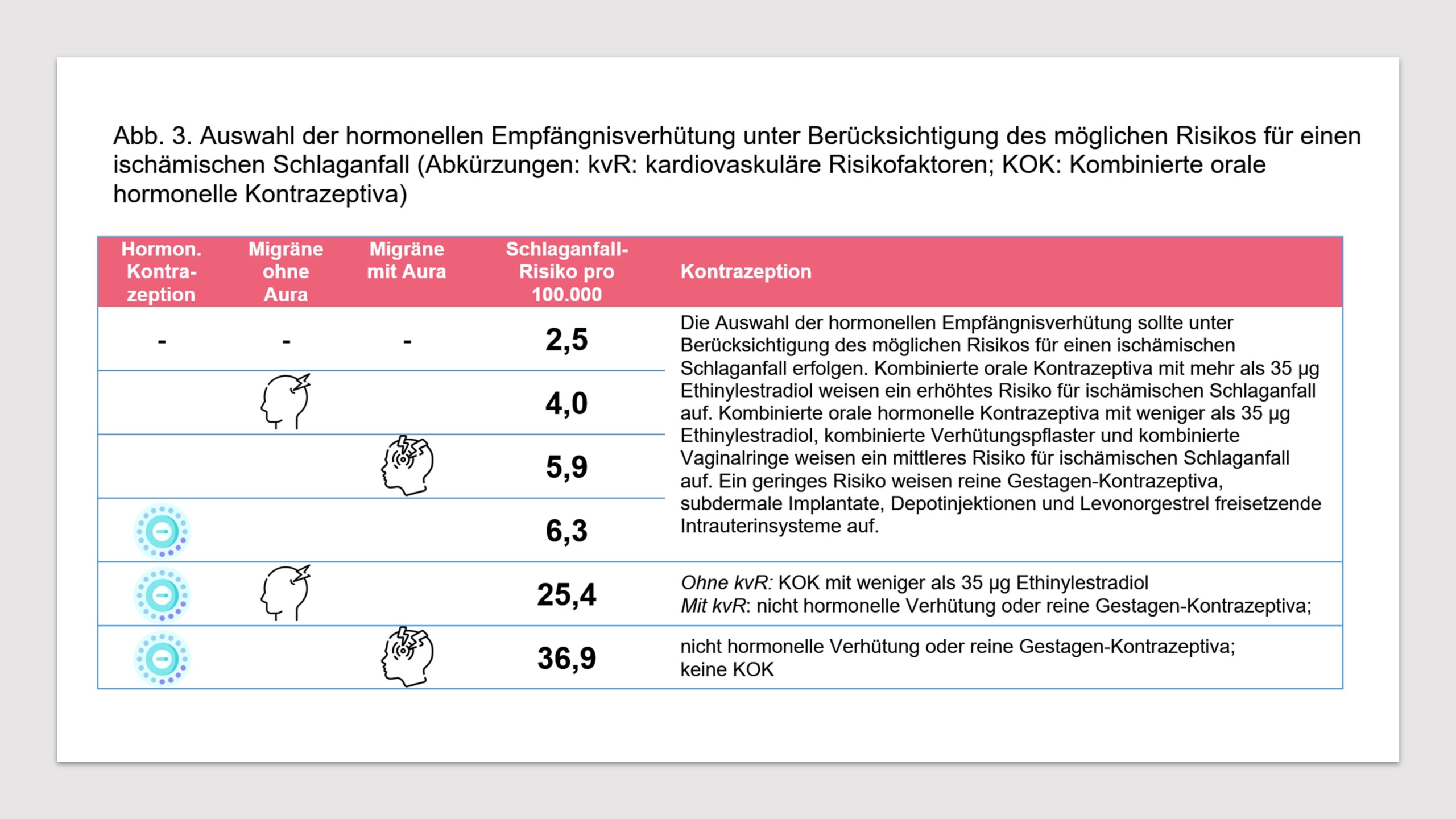

Hormonal contraceptives, stroke risk and migraine in practice

Migraine is a risk factor for stroke and other vascular events. Extensive evidence exists that an increased risk of ischemic stroke is associated with both migraine without aura and migraine with aura [4, 30, 32, 33, 58-60]. Since the risk of stroke may also be increased with the use of combined hormonal contraceptives [4, 32, 61], the question arises whether the coexistence of migraine and the use of combined hormonal contraceptives can further increase the risk of stroke. The European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESCRH) analyze this question in a consensus statement [33]. The absolute risk of ischemic stroke in women who do not use hormonal contraception is 2.5/100,000 per year. The same risk is 6.3/100,000 for women using hormonal contraceptives. For women with migraine with aura, the risk of an ischemic stroke without hormonal contraceptives is 5.9/100,000 per year. The risk of an ischemic stroke with migraine with aura and the use of hormonal contraceptives is 36.9/100,000 per year. For women with migraine without aura, the risk of ischemic stroke is 4.0/100,000 per year. If hormonal contraceptives are used in this group, the risk is 25.4/100,000 per year (see Fig. 3).

Based on the data, the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESCRH) derive the following expert consensus [33]:

- If women are seeking hormonal contraception, a clinical examination is recommended to analyze whether they have migraine with or without aura. Additionally, the frequency of migraine attacks (headache days per month) and the identification of vascular risk factors should be performed before prescribing combined hormonal contraceptives.

- Women who wish to use hormonal contraception are advised to use a special tool for diagnosing migraines and their subtypes. This can include questionnaires or digital options such as the migraine app (available for free download under this name in app stores).

- The choice of hormonal contraceptive should be made taking into account the potential risk of ischemic stroke. Combined oral contraceptives containing more than 35 µg of ethinylestradiol carry an increased risk of ischemic stroke. Combined oral hormonal contraceptives containing less than 35 µg of ethinylestradiol, combined contraceptive patches, and combined vaginal rings carry a moderate risk of ischemic stroke. Progestogen-only contraceptives, subdermal implants, depot injections, and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems carry a low risk.

- Women who suffer from migraine with aura and who wish to use hormonal contraception are advised against being prescribed combined hormonal contraceptives.

- Women suffering from migraine with aura who wish to use contraception are advised to use non-hormonal methods (condoms, copper IUDs, or progestin-only contraceptives) as the preferred option. If migraine with aura is present and combined hormonal contraceptives are already being used, switching to non-hormonal or progestin-only contraceptives is recommended.

- For women suffering from migraine without aura who wish to use hormonal contraception but have additional risk factors (smoking, arterial hypertension, obesity, cardiovascular disease, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in the past), non-hormonal contraception or progestogen-only contraceptives are recommended as the preferred option.

- For women suffering from migraine without aura who use hormonal contraceptives and have no additional risk factors, the use of combined hormonal contraceptives with a dose of less than 35 µg ethinylestradiol is recommended for contraception. Simultaneously, monitoring of migraine frequency and characteristics should be performed.

- If women suffer from migraine with aura or migraine without aura and require hormone treatment due to polycystic ovary syndrome or endometriosis, it is recommended that hormone treatment with progestogens only or combined hormonal contraceptives be used according to clinical considerations.

- If women who start using combined hormonal contraceptives develop new-onset migraine with aura, or who experience migraine without aura for the first time in close temporal relation to starting the hormonal contraceptive, a switch to non-hormonal contraceptives or progestogen-only contraceptives is recommended.

- If women suffering from migraine with or without aura require emergency contraception, the use of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg orally, ulipristal acetate 30 mg orally, or a copper-containing intrauterine device is recommended.

- If women with migraine with or without aura begin using hormonal contraception, specific tests such as thrombophilia screening, examination for patent foramen ovale, or imaging procedures are not relevant for the decision regarding hormonal contraception, unless the medical history or findings require such investigations based on specific indications.

- Any low-dose hormonal contraceptive can be used in women with non-migraine headaches who wish to use hormonal contraception.

Overall, the evidence regarding the link between ischemic stroke and the use of hormonal contraceptives is limited. Essentially, only uncontrolled observational studies exist. Further studies are needed to more precisely determine the potential risk of hormonal contraceptives in women with migraine. Nevertheless, the current data indicate an increased risk of ischemic stroke associated with the use of hormonal contraceptives in women with migraine. In this situation, it is essential that safety aspects are given particular attention during use. Even if the absolute risk of stroke is not very high, a stroke can have catastrophic consequences for individuals and their families. For these reasons, alternative contraceptive methods should be considered when there is a correspondingly increased risk.

literature

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS), The International Classification of Headache Disorders ICHD-3, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia, 2018. 38 (1): p. 1-211.

- Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Cephalalgia, 1988. 8 Suppl 7 : p. 1-96.

- The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia, 2004. 24 Suppl 1 : p. 9-160.

- Nappi, RE, et al., Role of Estrogens in Menstrual Migraine. Cells, 2022. 11 (8).

- Russell, MB, Genetics of menstrual migraine: the epidemiological evidence. Curr Pain Headache Rep, 2010. 14 (5): p. 385-8.

- Somerville, BW, The role of estradiol withdrawal in the etiology of menstrual migraine. Neurology, 1972. 22 (4): p. 355-65.

- Pavlović, JM, et al., Sex hormones in women with and without migraine. Neurology, 2016. 87 (1): p. 49.

- Cornil, CA, GF Ball, and J. Balthazart, Functional significance of the rapid regulation of brain estrogen action: where do the estrogens come from? Brain Res, 2006. 1126 (1): p. 2-26.

- Boese, AC, et al., Sex differences in vascular physiology and pathophysiology: estrogen and androgen signaling in health and disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2017. 313 (3): p. H524-h545.

- Rodriguez-Acevedo, AJ, et al., Genetic association and gene expression studies suggest that genetic variants in the SYNE1 and TNF genes are related to menstrual migraine. J Headache Pain, 2014. 15 (1): p. 62.

- Vetvik, KG and EA MacGregor, Menstrual migraine: a distinct disorder needing greater recognition. Lancet Neurol, 2021. 20 (4): p. 304-315.

- Shughrue, PJ and I. Merchenthaler, Estrogen is more than just a “sex hormone”: novel sites for estrogen action in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. Front Neuroendocrinol, 2000. 21 (1): p. 95-101.

- Facchinetti, F., et al., Neuroendocrine evaluation of central opiate activity in primary headache disorders. Pain, 1988. 34 (1): p. 29-33.

- Tassorelli, C., et al., Changes in nociceptive flexion reflex threshold across the menstrual cycle in healthy women. Psychosom Med, 2002. 64 (4): p. 621-6.

- Krause, DN, et al., Hormonal influences in migraine – interactions of estrogen, oxytocin and CGRP. Nat Rev Neurol, 2021. 17 (10): p. 621-633.

- De Icco, R., et al., Modulation of nociceptive threshold by combined hormonal contraceptives in women with estrogen-withdrawal migraine attacks: a pilot study. J Headache Pain, 2016. 17 (1): p. 70.

- Warfvinge, K., et al., Estrogen receptors α, β and GPER in the CNS and trigeminal system – molecular and functional aspects. J Headache Pain, 2020. 21 (1): p. 131.

- Kitazawa, T., et al., Non-genomic mechanism of 17 beta-oestradiol-induced inhibition of contraction in mammalian vascular smooth muscle. J Physiol, 1997. 499 (Pt 2) (Pt 2): p. 497-511.

- Somjen, GG, Mechanisms of spreading depression and hypoxic spreading depression-like depolarization. Physiol Rev, 2001. 81 (3): p. 1065-96.

- Edvinsson, L., et al., CGRP as the target of new migraine therapies – successful translation from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Neurol, 2018. 14 (6): p. 338-350.

- Knight, YE, L. Edvinsson, and PJ Goadsby, 4991W93 inhibits release of calcitonin gene-related peptide in the cat but only at doses with 5HT(1B/1D) receptor agonist activity? Neuropharmacology, 2001. 40 (4): p. 520-5.

- Ashina, M., Migraine. N Engl J Med, 2020. 383 (19): p. 1866-1876.

- Forbes, RB, M. McCarron, and CR Cardwell, Efficacy and Contextual (Placebo) Effects of CGRP Antibodies for Migraine: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Headache, 2020. 60 (8): p. 1542-1557.

- Drellia, K., et al., Anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies for migraine prevention: A systematic review and likelihood to help or harm analysis. Cephalalgia, 2021. 41 (7): p. 851-864.

- Valdemarsson, S., et al., Hormonal influence on calcitonin gene-related peptide in man: effects of sex difference and contraceptive pills. Scand J Clin Lab Invest, 1990. 50 (4): p. 385-8.

- Gupta, P., et al., Effects of menopausal status on circulating calcitonin gene-related peptide and adipokines: implications for insulin resistance and cardiovascular risks. Climacteric, 2008. 11 (5): p. 364-72.

- Aggarwal, M., V. Puri, and S. Puri, Effects of estrogen on the serotonergic system and calcitonin gene-related peptide in trigeminal ganglia of rats. Ann Neurosci, 2012. 19 (4): p. 151-7.

- Cetinkaya, A., et al., Effects of estrogen and progesterone on the neurogenic inflammatory neuropeptides: implications for gender differences in migraine. Exp Brain Res, 2020. 238 (11): p. 2625-2639.

- Yamanaka, G., et al., Role of Neuroinflammation and Blood-Brain Barrier Permutability on Migraine. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22 (16).

- Cupini, LM, I. Corbelli, and P. Sarchelli, Menstrual migraine: what it is and does it matter? J Neurol, 2021. 268 (7): p. 2355-2363.

- MacGregor, EA, et al., Incidence of migraine relative to menstrual cycle phases of rising and falling estrogen. Neurology, 2006. 67 (12): p. 2154-8.

- Sacco, S., et al., Effect of exogenous estrogens and progestogens on the course of migraine during reproductive age: a consensus statement by the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESCRH). J Headache Pain, 2018. 19 (1): p. 76.

- Sacco, S., et al., Hormonal contraceptives and risk of ischemic stroke in women with migraine: a consensus statement from the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESC). J Headache Pain, 2017. 18 (1): p. 108.

- Merki-Feld, GS, et al., Improvement of migraine with change from combined hormonal contraceptives to progestin-only contraception with desogestrel: How strong is the effect of taking women off combined contraceptives? J Obstet Gynaecol, 2017. 37 (3): p. 338-341.

- Morotti, M., et al., Progestogen-only contraceptive pill compared with combined oral contraceptive in the treatment of pain symptoms caused by endometriosis in patients with migraine without aura. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2014. 179 : p. 63-8.

- Morotti, M., et al., Progestin-only contraception compared with extended combined oral contraceptive in women with migraine without aura: a retrospective pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2014. 183 : p. 178-82.

- Nappi, RE, et al., Effects of an estrogen-free, desogestrel-containing oral contraceptive in women with migraine with aura: a prospective diary-based pilot study. Contraception, 2011. 83 (3): p. 223-8.

- Coffee, AL, et al., Extended cycle combined oral contraceptives and prophylactic frovatriptan during the hormone-free interval in women with menstrual-related migraines. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2014. 23 (4): p. 310-7.

- Calhoun, AH, A novel specific prophylaxis for menstrual-associated migraine. South Med J, 2004. 97 (9): p. 819-22.

- Macgregor, EA and A. Hackshaw, Prevention of migraine in the pill-free interval of combined oral contraceptives: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study using natural estrogen supplements. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care, 2002. 28 (1): p. 27-31.

- LaGuardia, KD, et al., Suppression of estrogen-withdrawal headache with extended transdermal contraception. Fertil Steril, 2005. 83 (6): p. 1875-7.

- Calhoun, A., S. Ford, and A. Pruitt, The influence of extended-cycle vaginal ring contraception on migraine aura: a retrospective case series. Headache, 2012. 52 (8): p. 1246-53.

- de Lignières, B., et al., Prevention of menstrual migraine by percutaneous oestradiol. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed), 1986. 293 (6561): p. 1540.

- Dennerstein, L., et al., Menstrual migraine: a double-blind trial of percutaneous estradiol. Gynecol Endocrinol, 1988. 2 (2): p. 113-20.

- MacGregor, EA, et al., Prevention of menstrual attacks of migraine: a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Neurology, 2006. 67 (12): p. 2159-63.

- Martin, V., et al., Medical oophorectomy with and without estrogen add-back therapy in the prevention of migraine headache. Headache, 2003. 43 (4): p. 309-21.

- Magos, AL, KJ Zilkha, and JW Studd, Treatment of menstrual migraine by oestradiol implants. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 1983. 46 (11): p. 1044-6.

- Murray, SC and KN Muse, Effective treatment of severe menstrual migraine headaches with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and “add-back” therapy. Fertil Steril, 1997. 67 (2): p. 390-3.

- Ferrante, F., et al., Phyto-oestrogens in the prophylaxis of menstrual migraine. Clin Neuropharmacol, 2004. 27 (3): p. 137-40.

- Burke, BE, RD Olson, and BJ Cusack, Randomized, controlled trial of phytoestrogen in the prophylactic treatment of menstrual migraine. Biomed Pharmacother, 2002. 56 (6): p. 283-8.

- Eikermann-Haerter, K., et al., Androgenic suppression of spreading depression in familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 mutant mice. Ann Neurol, 2009. 66 (4): p. 564-8.

- Nappi, RE, K. Wawra, and S. Schmitt, Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2006. 22 (6): p. 318-23.

- MacGregor, EA, Menstrual and perimenopausal migraine: A narrative review. Maturitas, 2020. 142 : p. 24-30.

- Schoretsanitis, G., et al., Drug-drug interactions between psychotropic medications and oral contraceptives. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol, 2022. 18 (6): p. 395-411.

- Lazorwitz, A., et al., Effect of Topiramate on Serum Etonogestrel Concentrations Among Contraceptive Implant Users. Obstet Gynecol, 2022. 139 (4): p. 579-587.

- Ornello, R., et al., Menstrual Headache in Women with Chronic Migraine Treated with Erenumab: An Observational Case Series. Brain Sci, 2021. 11 (3).

- Pavlovic, JM, et al., Efficacy and safety of erenumab in women with a history of menstrual migraine. J Headache Pain, 2020. 21 (1): p. 95.

- Adewuyi, EO, et al., Shared Molecular Genetic Mechanisms Underlie Endometriosis and Migraine Comorbidity. Genes (Basel), 2020. 11 (3).

- Saddik, SE, et al., Risk of Stroke in Migrainous Women, a Hidden Association: A Systematic Review. Cureus, 2022. 14 (7): p. e27103.

- Siao, WZ, et al., Risk of peripheral artery disease and stroke in migraineurs with or without aura: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Int J Med Sci, 2022. 19 (7): p. 1163-1172.

- Champaloux, SW, et al., Use of combined hormonal contraceptives among women with migraines and risk of ischemic stroke. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2017. 216 (5): p. 489.e1-489.e7.

- Hormonal Contraception Guideline of the DGGG, SGGG and OEGGG (S3 level, AWMF Registry No. 015/015, November 2019). https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/015-015.

- Diener, H.-C., et al., Therapy of migraine attacks and migraine prophylaxis, S1 guideline, 2022, DGN and DMKG , in Guidelines for diagnostics and therapy in neurology , DGfN (ed.), Editor. 2022: Online: www.dgn.org/leitlinien .

PDF Download Publication Pain Medicine 02 2023

Leave a comment