It was already proven 75 years ago that the large arterial and venous blood vessels in the meninges are sensitive to pain - unlike the brain tissue itself. 25 years ago, neuropeptides, i.e. proteins released from nerve fibers, were identified that regulate the width of these blood vessels. One of these substances was CGRP (the calcitonin gene-related peptide ). CGRP is one of the most powerful vasodilators in the body. At the same time, the vasodilation associated with CGRP is accompanied by pain in the experiment.

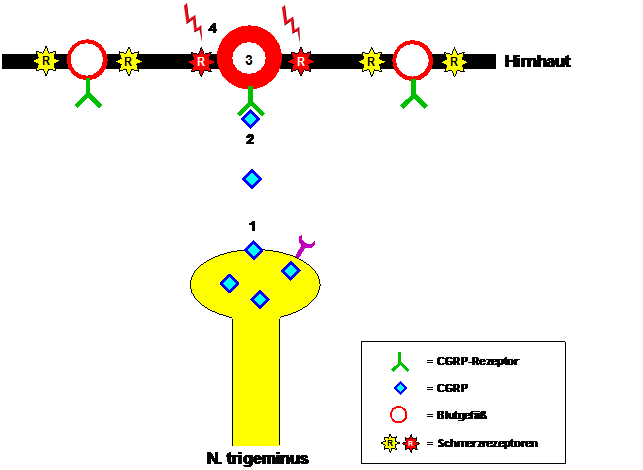

The crucial importance of CGRP in the development of migraines became apparent when elevated CGRP levels were found in the venous blood of patients during migraine attacks, which returned to normal after the migraine was stopped by administration of sumatriptan. These observations were confirmed when patients were able to induce migraine attacks by infusing CGRP. CGRP is formed, among other things, in nerve fibers of the trigeminal nerve and released when they are activated during a migraine attack (see Figure 1). The released CGRP binds to CGRP receptors in the wall of blood vessels in the meninges. This causes blood vessels to dilate and, at the same time, pain receptors in the blood vessel wall to become sensitized. The pulsation of the dilated blood vessels becomes a pain stimulus, which patients perceive as a pulsating, throbbing migraine pain that intensifies with any physical exertion, usually just by bending over.

Figure 1: Migraine pain mediation by CGRP. During a migraine attack, CGRP (1) is released from fibers of the trigeminal nerve, binds to the CGRP receptor (2), triggers dilation of blood vessels in the meninges (3) and finally leads to sensitization of pain receptors (4). react to the pulsation of the neighboring blood vessels with the sensation of throbbing migraine pain.

Triptans bind to certain serotonin receptors located on the endings of the trigeminal fibers and inhibit the release of CGRP during a migraine attack. It still takes some time until the previously released CGRP is broken down, the blood vessels narrow again and the pain receptors have regained their normal (in)sensitivity. Then the migraine is initially interrupted for the patient. This makes it clear that triptans help faster and more strongly the earlier you take them in the attack and the less CGRP has already been released. However, it is also understandable that triptans do not stop migraine attacks. CGRP continues to be formed, just not released temporarily. The CGRP accumulates in the trigeminal fibers and basically just waits for the triptans to be broken down. The then possible and sometimes massive release of CGRP leads to the recurrence of migraine pain in patients, the so-called recurring headache. Taking a triptan again is usually effective again. The whole game is repeated until the migraine attack actually subsides, usually after 4 to 72 hours. As an alternative to triptans, drugs were tested a few years ago that did not block the release of CGRP, but rather the CGRP receptor. The released CGRP therefore found no target in migraine attacks. These CGRP receptor antagonists were similarly effective as the triptans, but unfortunately caused liver damage when taken regularly in higher doses, so they never reached market maturity.

Figure 2: Migraine attack treatment with triptans and CGRP receptor antagonists. Triptans bind to serotonin receptors on trigeminal nerve endings (5) and thereby inhibit CGRP release (6). The CGRP-mediated migraine symptoms subside. The same effect can be achieved by blocking the CGRP receptor with a CGRP receptor antagonist (8). The problem with triptans is that - even when the migraine seems to have ended - CGRP continues to be formed (7) and is then released after the triptan effect has worn off. A recurring headache occurs.

The introduction of triptans was undoubtedly a decisive advance in migraine attack therapy. So far, it has not been possible to achieve similar success in preventing migraines. None of the preventive medications used today were specifically developed . All medications were initially used for other illnesses, such as beta blockers to treat blood pressure, and have a more or less unfavorable benefit-side effect ratio. This is set to change in the future and the CGRP will once again play a crucial role.

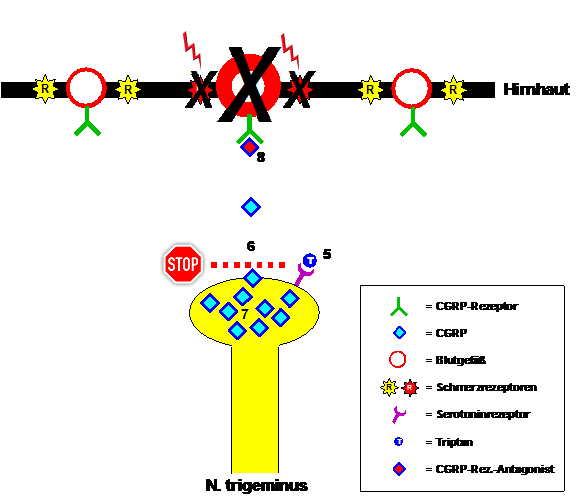

Clinical studies are currently being carried out with the participation of the Kiel Pain Clinic, in which monoclonal antibodies are used to prevent migraines, which either destroy the CGRP released in migraine attacks or use the CGRP receptor to destroy its target. The patients are passively vaccinated against migraines. The antibodies are injected under the skin once a month. The initial study results are promising - the substances are significantly more effective than placebo and are well tolerated so far. But what gives particular hope for the future is that in the published phase II studies, a small group of patients became completely free of migraine attacks. It remains to be seen whether the results will be confirmed and, above all, permanent.

Figure 3: Target of monoclonal antibodies for migraine prophylaxis. The antibodies are injected under the skin once a month and then destroy either the CGRP released in migraine attacks (9) or the CGRP receptor (10). In theory, migraine attacks should remain painless due to the elimination of the CGRP effect.

Dr. Axel Heinze, Dr. Katja Heinze-Kuhn, Prof. Dr. Hartmut Göbel, Kiel Pain Clinic

Addendum: Many readers ask whether participation in the study is possible. The project provides for defined criteria for participation, which we have to check individually. This is an international study. In order for the results to be comparable worldwide, only a limited number of participants can be selected in the individual centers. This usually requires longer courses of treatment in our outpatient care.

I agree that I have been suffering from migraines for many years and it just won't stop. Sometimes nothing helps and the emergency services even have to be called. I would also like to get vaccinated and hope that it will stop at some point.

I have suffered from migraines since I was 18.

Today I am 59 years old and have tried so many things - grasping at every straw. However, I also became a bit discouraged because of all the many failed attempts. I am currently being treated with Botox. This means I went from at least 15 to 20 days of pain a month to an average of 12 - 15 days of difficulty. That's a bit of a relief. Things get bad when the 10 triptans per month are 'used up' and I have to endure the pain for the rest of the month. Sometimes I feel like I'm struggling through life. A vaccination against migraines - which my neurologist has already told me about - would be fantastic and the chance for a better quality of life for so many people.

If further studies are carried out in Germany and subjects are sought for them... I would be very happy to take part in them.

I have also been suffering from migraines for over 30 years, once with aura and mostly without aura. It is a pain and drives you into depression. You can't plan anything properly, it is difficult to hold out in the job. It comes indefinitely. This does not cope with everyday stress. You can only find understanding under like -minded people. I would also make myself available with the vaccination so that life could finally become more livable again.

I would also be available as a test subject for this study!!!!

Because of my change, I also have a lot more attacks and a diagnosed vertigo migraine. Even one less day without a migraine is a day gained. My greatest and most fervent wish would also come true for me.

I've been suffering from migraines for 40 years and the frequency increases from year to year - about 20 times a month - you take the pain by fainting, your family, friends and colleagues suffer from it.

When I saw the report during the visit, I almost cried because I was hoping for a pain-free future, if, like many people here, I would

immediately be able to take part as a test person.

Are there still miracles??

I would also take part in the study immediately... I have 30 pain days a month -.-

I would very much like to take part in this study.

I have had migraines since I was a child.

Every therapy was unsuccessful for me. My migraines are very bad because no medication helps anymore. I often lie in bed feeling lifeless and every member of my family suffers from it. Maybe this treatment would be a relief for me and also for my family! Kind regards from Frankfurt!

I'm really jealous of your comments o.0 I've been diagnosed with it since I was 5 or 6 and I have migraines up to 25 days a month... I'm also really waiting for the medication and I would do anything to give myself peace of mind ... I'm just postponing the operation with the tubes because of the medication... But 5 times a month is almost a good result oO

I have been suffering from migraines for 38 years now. I've been living with it longer in my life than without it. I can't even list what I've done, but I grasped at straws. Without success. I hate how migraines take over my/our life. In the end, you always resort to triptans in order to be able to work and participate to some extent in life. The vaccination, I can't believe it, would be the greatest gift for me after so long.

I agree with the comments of my predecessors. After decades of pain and numerous therapies, this therapy/vaccination would be a relief. We all struggle and we all need treatment that gives us back our quality of life. We move from day to day and week to week, and every minute of our lives is overshadowed by migraines. The psyche, the soul and the body suffer. Each of us deserves a medal for the achievements we accomplish despite pain. Also the people who research migraines on our behalf. Thanks.

I would also be there - being 14 years old - and as I said - no one would believe how this would affect everyday life.

It's not just the patient who suffers - children, partners, colleagues - that no one judges

I would pay for a vaccination immediately because I have had migraines with aura for 35 years and have had attacks much more frequently each month since about a year ago when I went through menopause.

I would be there right away too. It's unimaginable to be free again after suffering from migraines for several years. Just live and enjoy the day.

Pain-free for over 350 days a year? That sounds too good to be true!!!!!!!!!!!!

That would be a dream!!!After almost 30 years and 4-5 migraines a month, finally without pain!!! I would also be ready for the study immediately.

Painless what a nice word…………

I have suffered from very severe migraines since I was 17.

I am now 56 and have just had migraines for 3 days in a row. I get 18 Maxalt migraine tablets and 4 Imigran injections every quarter, which makes everyday life more bearable for me. I would also be happy to finally get rid of my unbearable attacks by making myself available as a test subject. To finally be pain-free and just take part in life again would be my dream too.

Dear clinicians,

the idea of having the prospect of less pain after around 60 years borders on paradisiacal conditions.

Like many others, I would immediately offer myself as a test person. Maybe it will work. All the best to us fellow sufferers

Gunnar Thiem

That sounds like a fairy tale, it would be a revolution, one vaccination a month and everything is fine...

I would also get vaccinated every week as long as I don't have to worry about a migraine attack anymore!!!!! Being able to enjoy life again, no longer having to have a bad conscience towards your colleagues and and and...,,,,,! Would love to be there!!!!!!

I would also immediately make myself available as a candidate! I've also had migraines for as long as I can remember, and it seems to me that I'm becoming more and more sensitive, or rather the migraines are occurring more and more often, seemingly for no reason! I tried all the migraine prophylaxis and stopped everything again because it just didn't work. So how can you take part in the study? The comments start in March 15? Today, when I came to this page because I'm having migraines again, it's September 19th, 2016!

I'll be there right away too! A life without pain sounds almost too good...

I am also very interested in participating as a test person and escaping the vicious circle

Dear Prof. Dr. Hartmut Göbel, dear Drs. Axel Heinze and Katja Heinze-Kuhn,

I agree with the many hopes expressed by commentators. May I make a suggestion about your very interesting and informative statements? The article talks about, among other things, the results of the published phase II studies. I would be very interested in the proposed timeline for further planning (Phase III, date of completion of the approval dossier, expected approval date).

Based on my findings, hope plays a large role in migraine treatment. For example, an improvement was also achieved in the test group that only received a placebo injection. I am 59 years old and take an average of 8 to 10 triptans per month. Since these remedies are no longer so popular after the age of around 65, I am of course already thinking about what will happen in a few years. At the moment there is no real alternative to triptans for me. This already makes the idea of no longer being able to take these drugs in a few years a tormenting thought. Therefore, for me (and I think I speak on behalf of many commentators here) the timeline for further planning is of great interest. Who knows, perhaps just the concrete prospect of help - even if it is still in the future - will help to improve the situation today. I cannot rule this out for myself. It is not for nothing that it is said: “Hope dies last”.

Kind regards and good luck

I was watching the NDR visit yesterday and saw that there should now be a vaccination against migraines. I would get vaccinated immediately, since the menopause with a lot of grief I have been suffering from migraines almost every day. Sometimes they are weaker, sometimes strong, but they are always there. They slowly disappear My strength and my quality of life are so severely limited that sometimes I don't feel like it anymore. I'm 56 years old and I'm wondering what's going to happen next. If there was a drug like that, it would be great. It's a shame that we as normal citizens have to do that I always find out too late. It would be a dream to be without pain and weakness again. I'm going to be a grandma for the first time and it makes me very sad that I won't be healthy enough for it

Dear Professor Göbel,

For my part, I wish you and the other participating doctors much, much success. It would be a revolution in migraine therapy. I am looking forward to it.

Many kind regards,

S. Ritter

It's unbelievable how many people experience the same thing, and yet you hardly ever meet like-minded people in everyday life! After 30 years of migraines and all possible treatments and medications that have never worked, this study gives me incredible hope! I've had a little son for 9 months and as you can imagine, a child and a migraine are the shittiest combination there is. I really hope that one day I won't have to be afraid of the attacks anymore and can enjoy life the way pain-free people can!

I've been suffering from migraines for years and can't tolerate the tablets very well. Both of our daughters also have migraines. I'm always afraid to take the pill because it makes me sick and my circulation is in trouble. I would very much like to take part as an intern.

Was treated at the Kiel Pain Clinic last year in September 2015. I have a chronic migraine!!!! Living with this is very difficult. No matter at work or in my private life! I would do anything to be relatively healthy!!!! As a test subject I would be there straight away...

A LIFE without PAIN - simply fantastic.

That would be nice – to have a “normal” head, to be able to sleep restfully and simply experience the day… every day!

Please hold the line!

I have been suffering from migraines for about 26 years and would like to volunteer as a test subject! A life without migraines!!!Unimaginable, brilliant, wonderful...

I would be there in a heartbeat too! Miserable pain half the week, 52 weeks a year, no one can stand that! Free at last!

I've suffered from migraines with nausea since childhood and vomiting is always a horror, and it's been like this for almost 30 years. I've been taking citalopram for panic attacks for a few years. And I'm afraid to try triptans because of interactions. Other medications don't help me. That means I can handle it every time without medication. I have an attack about 1-2 times a month and then I just lie in bed and throw up. So a life without migraines would be a dream, my greatest wish.

That would be a blessing!

I have been suffering from migraines for 50 years, plus depression 10 years ago. I would immediately make myself available as a test person in order to get a normal quality of life. This invention would be a blessing!

After about 28 years of migraines and having checked off all prophylactic medications, I would love to get a vaccination once a month and avoid the migraines. I hope it will soon be a method accessible to everyone.

I was diagnosed with chronic migraines.

I would immediately make myself available as a test subject.

Unbelievable, so many comments, almost all of which you could have written yourself. I'm 42 and have had migraines for as long as I can remember. I stay afloat with beta blockers and when I have attacks (currently 2 a week), I take Allegro. The quality of life and desire for life decreases from year to year - help through a vaccination sounds too good to be true. If you've already tried everything you can to treat migraine, it's difficult to hope to lead a carefree life again. I live south of Munich and would immediately make myself available as a probationer.

Prof. Göbel, it's good that there are doctors like you who continue to research and know what migraine pain means - thank you!

I was also in your clinic in 2010 and coped much better with the newly prescribed medication and had fewer migraines and less pain. Had an almost good quality of life. Now the attacks are increasing again, I had terrible pain for three days and one night, and Novalgin suppositories and Maxalt refused to work for me. It would be wonderful if the vaccination worked. In the meantime, I was diagnosed with a 50% severe disability, perhaps important for other migraine sufferers.

I would also make myself available immediately. Side effects etc. would not matter, because they cannot be nearly as bad as almost 24 hours a day, 7 days a week to have headaches and migraines

I would also be happy to volunteer as a test subject. I have had migraines for 25 years and have tried many applications without much success. I have remained childless so far for fear of not being able to look after my child and of passing on this terrible disease. At times the illness has such a hold on me that I no longer feel my life is worth living.

Hello, Prof. Göbel,

I have been suffering from migraines since I was 10, i.e. for 45 years.

Since I am from June 2nd. If I'm in your clinic, I'd be happy to volunteer as a test person!

How nice that would be.

I suffer from headaches every day and have full-on migraine attacks every 3-5 days.

I'm afraid of passing this disease on to my children and have no children yet.

Wish everyone lots of hope and pain-free time.

Because hope dies last.

I have suffered from migraines for 30 years, usually 12-19 days a month. If this vaccination really helps and I get it, a long unfulfilled dream would come true for me and long suffering would come to an end. That would really be an advance in medicine that many migraine sufferers have longed for for a long time.

To finally live without pain, I would make myself available immediately

I've been suffering from migraines for 15 years, first only during my period, then the weather came along and now I'm almost at constant migraines. I would try it immediately to finally get rid of this pain, the quality of life is simply at zero.

I have been suffering from migraines for 30 years. I always took cafergot. Perfect for me! Various triptans didn't help. Never had any side effects from ergotamine. Family doctors are no longer allowed to write prescriptions in Austria because of ergotamine. I'm very, very desperate because cafergot is the only solution for me. I'm now taking eumitan, which doesn't help either. Need 3 tabs for relief and then it comes back again. Cafergot only half a suppository. Please who can help me??

I have had migraines with 15 attacks per month for 35 years. The report gave me hope. I would like to take part in such a study.

I have suffered from migraines with aura since I was 10 years old.

I have up to 20 seizures a month. I had a PFO closure done 4 years ago and am taking Plavix. After taking Plavix I no longer have an aura. But currently I have a migraine attack 2 to 3 times a week without aura. Take Allegro. The fear is that I won't be able to take the Plavix anymore. Then I would no longer be able to work (on the PC) because I have visual problems and other failures (speech problems) up to 20 times a day. A vaccination like this would be great.

To be normally resilient. A dream. I would make myself available as a test subject.

I have been a migraine sufferer since I was 15 years old and would be very interested in taking part and following the progress of this examination. I live in berlin.

Dear Mr. Prof. Göbel,

I am happy to read how you support migraine sufferers.

I (52) have been suffering from migraines for 46 years and have up to 20 attacks a month.

My joy in being alive is very “humble”! I think only my daughter (15 years old) is holding me up and I feel full of guilt towards her because I passed on migraines to my daughter.

Her first seizure was when she was 4 years old!! Unfortunately, Austria is a developing country when it comes to migraines.

There is a headache clinic in Vienna General Hospital, but you can't get an appointment (waiting time 2 years!).

Personally, I take Relpax 40mg - but I can't take more than 10 tablets a month.

This report from you “CGRP vaccination against migraines” is wonderful and gives hope - maybe not for me anymore,

but my daughter (15) may be able to improve her life through it.

I wish you all the best from the bottom of my heart

and best wishes from Vienna

All people who are against the pharmaceutical industry (and this happens very often) should experience what hope feels like when you have migraines almost every day and are only allowed to take triptans on 10 days. I'm currently on a triptan break and am experiencing hell on earth. The prospect of help, even if only in a few years, is simply wonderful. Thanks to everyone working on this drug!

Dear Prof. Göbel,

after more than 30 years of migraines, your report gives hope that you may soon be relieved. Be relieved from these migraine attacks that have dominated my life - and the lives of millions of people - for far too long. I would recommend you for the Nobel Prize in Medicine. :-)) Thank you very much for your years of commitment!

So far, women have complained about their suffering, but it also affects men.

I have suffered from migraines for 39 years.

I'm self-employed and work constantly, so I only have Sunday as a day off. I usually just lie around in bed when I have pain attacks. I even have a bed in my company that I can pull out of for attacks during the week. I get a lot out of life there, so I would like to volunteer as a test subject.

Dear Prof. Göbel,

I was only in your clinic in January/February 2015 and I am already feeling significantly better. In order to

finally get rid of the migraines, I would be happy to offer myself as a test person.

I have had severe migraines since childhood and would immediately volunteer for this study...

I just got home from my family and had this issue too….

I've been trying everything for over 15 years... I am now 37 years old and for months I have been having panic attacks before the next attack. I don't know how I got through this before without my miracle sumatriptan? If I “only” need 4-5 of them within 72 hours, it is a “good” attack. I would do almost anything for a cure. And I would even be happy to make myself available as a test subject! THE dream of all dreams would come true***

I'm 41 and have had migraines since I was a child. Unfortunately, five years ago, panic attacks and now depression also occurred. Since I also suffer from asthma, I am unable to prevent it with beta blockers. I would immediately offer myself as a guinea pig.

That would be revolutionary! Migraines for 65 years – would take part in the study immediately.

Hello, I would take part in the study immediately. I have suffered from migraines for 53 years, and they are particularly common at the moment. LG Charlotte Maslonka

If this works in the long term, it would be a blessing for all migraine sufferers...

I've already tried so many things, from conventional medicine to alternative medicine,

all without success... only my wallet has become a lot lighter.

Would take part in a study immediately……. I have been suffering from migraines almost every day for 13 years.

That would be great !

A blessing for the many people affected whose quality of life suffers!! After 45 years of migraines with currently 13 to 16 migraine days per month, I would like to use it!

A life without migraine pain? This is beyond my imagination... Heaven on Earth!!!

This would truly be a revolution. I would like to take part in this study. I have been suffering for more than 35 years now!

That would really be a dream come true - after 60 years with all kinds of medication...

Please provide more information about this method - thank you

Dear Prof. Göbel,

That would be so nice.

Suffer from chronic migraines. I would also immediately make myself available as a test person. I really hope for all migraine sufferers that this remedy has the success we all want!

too good to be true….would make myself available immediately…

“After 54 years of migraines, that was the main prize!

Prof. Göbel,

reading that was wonderful. Hopefully there won't be too many bureaucratic hurdles to overcome so that the injection treatment can be started as quickly as possible. As a former patient of your clinic, I would like to offer myself as a test person. Even with Botox, I have almost no relief.

I would immediately make myself available for experiments. After 42 years of migraines, I'm starting to get very tired

I would make myself available immediately. It would be a dream for me to be pain-free again.

I would join immediately!!! A dream... to finally live without pain!

43 years of hell in my head and therefore in my life. I would really like to take part in the study.

Finally pain free, that would be a wonderful gift, I would try it immediately!

That would have deserved the Nobel Prize!

Oh,

that would be a dream,

no more migraines :-)

That would be wonderful! I would try it immediately!

If this were really successful and one became or remained pain-free, it would be groundbreaking. I think every migraine sufferer would immediately volunteer to be a test person, including me.

A revolution in migraine pain management. I would make myself available immediately.

That would be a miracle after 37 years of migraines!!!

that'd be wonderful

a dream would come true