Numerous brain areas relevant to the pathophysiology of migraine, the cranial vascular system, the dura mater and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord express estrogen receptors. This allows painful stimuli to be modulated. Migraine attacks can occur in relation to the menstrual window. Migraine is a risk factor for stroke and other vascular events. There is extensive evidence that an increased risk of ischemic stroke is associated with both migraine without aura and migraine with aura. Since the risk of stroke can also be increased when using hormonal contraceptives, the question of what options for action exist in practice is important.

Classification of migraines in relation to menstruation

The current 3rd edition of the International Headache Classification ICHD3 [1], like the previous editions, has not allocated any space in the main part to migraine attacks that occur in relation to the menstrual window. The first edition in 1988 [2] did not list any formal criteria for migraine associated with menstruation. But already in this first edition it was noted in the comment section that for some women migraine attacks without aura can occur exclusively with menstruation. This was called “so-called menstrual migraine”. The term should only be used if at least 90% of the attacks occurred in the period 2 days before menstruation to the last day of menstruation. In the second edition of the international headache classification in 2004 [3], two subtypes of migraine in connection with menstruation were defined for the first time in the appendix. The so-called “pure menstrual migraine” refers to attacks that occur exclusively in connection with menstruation. In contrast, with the so-called “menstrual-associated migraine”, attacks also occur at other times of the cycle. Both forms were subgroups exclusively of migraine without aura. The appendix to the International Headache Classification describes research criteria for headache symptoms that have not yet been sufficiently validated by scientific studies. Both the experience of the members of the Headache Classification Committee and publications of varying quality suggest the existence of these entities listed in the appendix, which can be considered as distinct disorders but for which further scientific evidence needs to be provided before they can be formally accepted. If this is successful, these diagnoses from the appendix can be incorporated into the main part the next time the classification is revised.

In the 3rd edition of the international headache classification from 2018, “pure menstrual migraine” and “menstrual-associated migraine” are still only found in the appendix. Both diagnoses require that the migraine attacks occur on day 1 ± 2 of menstruation (ie, day −2 to +3) of menstruation in at least 2 of 3 menstrual cycles (Table 1, Fig. 1). However, the criteria have now been expanded to include a subtype with aura, although menstrual migraine attacks usually occur without auras. This defines pure menstrual migraine with and without aura as well as menstruation-associated migraine with and without aura. If the forms pure menstrual migraine and menstrual-associated migraine are combined, one speaks collectively of the so-called “menstrual migraine” [4].

Table 1. ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria for migraine within and outside the menstrual window

———————————————————————————

A1.1.1 Purely menstrual migraine without aura

- Attacks in a menstruating woman 1 that meet Migraine without aura

- The attacks occur exclusively on day 1 ± 2 (ie, day −2 to +3) of menstruation 1 in at least 2 of 3 menstrual cycles and at no other time of the cycle.

A1.1.2 Menstrual-associated migraine without aura

- Attacks in a menstruating woman that meet the criteria of 1.1 Migraine without aura and Criterion B below

- The attacks occur on day 1 ± 2 of menstruation ( ie, day −2 to +3) of menstruation in at least 2 of 3 menstrual cycles, but also at other times of the cycle.

A1.1.3 Non-menstrual migraine without aura

- Attacks in a menstruating woman that meet the criteria for 1.1 migraine without aura and criterion B below

- meet criterion B for A1.1.1 purely menstrual migraine without aura or A1.1.2 menstruation-associated migraine without aura

———————————————————————————

A1.2.0.1 Purely menstrual migraine with aura

- Attacks in a menstruating woman 1 that meet Migraine with aura

- The attacks occur on days 1 ± 2 of menstruation (ie days −2 to +3) of menstruation in at least 2 of 3 menstrual cycles, but also at other times of the cycle.

A1.2.0.2 Menstrual-associated migraine with aura

- Attacks in a menstruating woman that meet Migraine with aura

- The attacks occur on day 1 ± 2 of menstruation ( ie, day −2 to +3) of menstruation in at least 2 of 3 menstrual cycles, but also at other times of the cycle.

A1.2.0.3 Non-menstrual migraine with aura

- Attacks in a menstruating woman that meet Migraine with aura

- meet criterion B for A1.2.0.1 purely menstrual migraine with aura or A1.2.0.2 menstruation-associated migraine with aura

———————————————————————————

For the purposes of ICHD-3, menstruation is considered endometrial bleeding resulting from the normal endogenous menstrual cycle or withdrawal of external progestogens, the latter applying to combined oral contraceptives and cyclic hormone replacement therapy (Fig. 1). According to ICHD-3, the distinction between purely menstrual migraine without aura and menstruation-associated migraine without aura is important because hormone prophylaxis is more likely to be effective in the latter [1].

More than 50% of women with migraines report an association between menstruation and migraines [5]. The prevalence in different studies varies due to different diagnostic criteria. The prevalence of pure menstrual migraine without aura varies between 7% and 14% in migraine patients, while the prevalence of menstrual migraine without aura varies between 10% and 71% in migraine patients. About one in three to five migraine patients have a migraine attack without aura associated with menstruation [5]. Many women tend to overstate the connection between menstruation and migraine attacks; for research purposes, diagnosis requires prospectively documented evidence of a minimum of three cycles as evidenced by the migraine app or diary records [1].

The mechanisms of migraine may differ depending on whether the endometrial bleeding occurs as a result of the normal endogenous menstrual cycle or withdrawal of external progestins (as with combined oral contraceptives and cyclic hormone replacement therapy). The endogenous menstrual cycle results from complex hormonal changes in the axis of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland and ovaries, which trigger ovulation, which in turn is suppressed by taking combined oral contraceptives. These subpopulations should therefore be considered pathophysiologically separately, although the diagnostic criteria cannot be differentiated from one another.

There is evidence that in at least some women, menstrual migraine attacks may be triggered by estrogen withdrawal, although other hormonal or biochemical changes may also be relevant at this point in the cycle [4]. If pure menstrual migraine or menstrual-associated migraine are associated with exogenous estrogen withdrawal, both diagnoses, pure menstrual migraine without aura or menstrual-associated migraine without aura and estrogen withdrawal headache, should be given. The association with menstruation can change over the course of a woman's reproductive lifespan.

Effect of hormones on headaches

The effect of hormones on headaches was included in the main section “secondary headaches” in the 2004 2nd edition (ICHD-2) of the international headache classification [3]. The criteria concern headaches that have recently occurred in connection with hormone administration or pre-existing headaches that have worsened as a result. The criteria require that the headaches improve after the hormones are stopped or that the previous pattern recurs in the case of pre-existing headaches.

In the 3rd edition 2018 (ICHD-3) [1], the presence of headaches on at least 15 days per month was required for the diagnosis of a headache attributed to the administration of exogenous hormones. The diagnosis of estrogen withdrawal headache according to ICHD-3 requires that the headache begins within 5 days of estrogen discontinuation if women have taken estrogens for at least three or more weeks.

Estrogens and migraines

In 1972, Somerville described that intramuscular injection just before menstruation of estradiol valerate, a pro-drug ester of 17β-estradiol, can delay the onset of a menstrual-associated migraine attack [6]. A threshold concentration of circulating 17-β-estradiol of 45-50 pg/ml has been identified, below which a migraine attack can be triggered. This threshold was also evident in menopausal women who had undergone hormone replacement therapy with intramuscular 17β-estradiol. Based on these data, it was hypothesized that migraine attacks in the menstrual window are triggered by a drop in estrogen. Based on this, it was postulated that physiological estrogen fluctuations play a role in the development of migraines. This assumption was supported by the finding that a particular susceptibility to migraine attacks occurs during the estrogen decline in the late luteal phase. However, differences in the maximum values or the average daily concentration value of estrogen during ovulation cycles in migraine patients compared to healthy controls could not be demonstrated [4, 7].

Estrogen and nervous system

The most relevant endogenous estrogen is 17β-estradiol [8]. It has access to the central nervous system through passive diffusion through the blood-brain barrier. However, it can also be synthesized locally in the brain from cholesterol or from aromatized precursors by the enzyme aromatase and act there as a neurosteroid. The physiological effects may be due to activation of various estrogen receptors, in particular estrogen receptor-α (ERα), estrogen receptor-β (ERβ), and G protein-coupled estrogen receptor-1 (GPER/GPR30) [ 9].

Estrogens develop their biological effects in the central nervous system through genomic or nongenomic cellular mechanisms. This can alter neurotransmission and cell function. Intracellular signaling cascades can modify enzymatic reactions, ion channel conductivity and neuronal excitability [4].

Numerous brain areas involved in the pathophysiology of migraine express estrogen receptors. This is particularly true for the hypothalamus, the cerebellum, the limbic system, pontine nuclei and the periaqueductal gray (substantia grisea periaquaeductalis). Estrogen receptors are also expressed in the cerebral cortex, which can modulate pain sensitivity afferently and efferently. The cranial vascular system, the dura mater and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord also express estrogen receptors, which can modulate painful stimuli [4, 8, 9].

Genome-wide association studies showed no correlation between estrogen receptor polymorphisms and an increased risk of migraine. However, a single nucleoid polymorphism in the SYNE1 gene was found to be associated with menstrual migraine [10].

The serotoninergic system can be activated by estrogen, which can have a protective effect against migraine attacks [11]. Estrogen can also increase the excitatory effects of glutamate. This may explain the increased likelihood of migraine aura developing during periods of high estrogen concentrations, such as during pregnancy or when receiving exogenous hormones.

Estrogen can modulate the γ-aminobutyric acid system (GABA), which has an inhibitory effect in the nervous system [12]. Progesterone, which is mainly produced by the corpus luteum of the ovaries, and its metabolite allopregnanolone can enhance GABAergic activity and thus cause an antinociceptive effect.

Estrogens can also modulate the endogenous opioid system through increased synthesis of enkephalin [13]. Accordingly, decreased estrogen and progesterone levels during the late luteal phase may be correlated with reduced activation of the opioid system. This causes increased sensitivity to pain. Studies on pain sensitivity during the different phases of the menstrual cycle showed increased sensitivity during the luteal phase, especially in women complaining of premenstrual symptoms [14]. High estrogen concentrations also promote the formation of other pain-inhibiting neurotransmitters and neuropeptides, such as neuropeptide Y, prolactin and vasopressin, which can play a role in the development of migraines [4].

Oxytocin and migraines

The neuropeptide oxytocin is produced in the hypothalamus. It has extensive effects in the central nervous system. In particular, it modulates mood and behavior. It influences the body's own pain control and can have a migraine preventive effect [4]. During phases of increased estrogen concentrations, oxytocin levels are also increased. Estrogen leads to increased production of oxytocin in the hypothalamus and other brain areas, especially in the trigeminal nucleus caudalis [15]. Women suffering from menstrual migraine show reduced pain thresholds during the hormone-free phase when taking combined hormonal contraceptives, i.e. at the time when estrogen concentrations are reduced [16].

The pathophysiology of migraine is associated with increased cortical nociceptive activity in the trigeminovascular nociceptive system. This causes both vasodilatation of the intracranial vessels and meningeal inflammation [15]. The local activation of estrogen receptors in the trigeminal ganglion may lead to the triggering of migraine attacks. Women have more estrogen receptors in the trigeminal ganglion than men [17]. Estrogens can acutely influence vascular tone by inhibiting smooth muscle calcium channels [18]. Cortical spreading depression (CSD) can also be activated by estrogens. This results in cortical neuronal depolarization, which is considered a characteristic feature of migraine with aura [19]. High levels of estrogen increase susceptibility to CSD, estrogen withdrawal reduces susceptibility to CSD. This could explain why migraine attacks in the menstrual window are less often associated with aura [1].

Estrogens and calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRP)

The release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is now considered a crucial step in the pathophysiology of migraine. Stimulation of the trigeminal ganglion can lead to a release of CGRP and substance P into the cranial blood circulation [20]. CGRP activates nociceptive mechanisms in the dura, trigeminal ganglion, cervical trigeminal nucleus complex, thalamus and periaquaductal gray, among others [20]. Both the clinical symptoms of migraine and the release of CGRP can be blocked by triptans [21]. CGRP infusions can provoke an attack in migraine patients [22]. This is not the case in healthy controls. Monoclonal antibodies that specifically target the CGRP as a ligand (eptinezumab, fremanezumab and galcanezumab) or the CGRP receptor (erenumab) are now available in healthcare for the preventive treatment of episodic and chronic migraine [23, 24]. They have been shown to be effective and tolerable in controlled studies.

CGRP levels are higher in women than in men [25]. They are also increased during pregnancy and when combined hormonal contraceptives are given. During menopause, levels are variable [26]. CGRP receptors and estrogen receptors are expressed in the same brain areas. Estrogen can modulate CGRP production in trigeminal neurons. Experimentally, the administration of exogenous estrogen leads to reduced CGRP levels [27]. During postmenopause, CGRP levels may be increased while estrogen concentrations are reduced [28].

As a vasoactive neuropeptide, substance P can also cause neurogenic inflammation in the meninges in connection with migraines [28]. Estrogen administration may reduce plasma levels of substance P. In summary, estrogen can modulate both CGRP and substance P through inhibitory effects. Estrogen therefore provides a protective mechanism against neurogenic inflammation [28]. In addition, estrogen can inhibit the activating effect of progesterone on CGRP and substance P. This indicates that the combination of estrogen and progesterone has a stabilizing effect on CGRP and substance P release [4].

Migraine patients exhibit increased levels of proinflammatory cytokinins both during the migraine attack and in the interval [29]. Experimental studies indicate that estrogens can inhibit circulating inflammatory molecules. In addition, they have a protective effect against prostaglandin-induced inflammation. In contrast, estrogen withdrawal can increase sensitivity to prostaglandins and activate neuroinflammation through increased release of neuropeptides such as CGRP, substance P and neurokinin [30].

In summary, the available data indicate that estrogen in itself does not have a direct protective effect on migraine attacks. However, estrogen can indirectly influence activating and inhibiting migraine factors. As a result, the initiation of migraine attacks in the neurovascular area can be inhibited. In the trigemino-vascular circulation, the sensitivity to migraine can be reduced. If estrogen concentrations are reduced, the threshold for migraine attacks can be lowered [4, 15].

Estrogens in the prevention of menstrual migraines

In some patients, migraine attacks may only occur during the menstrual window [1]. The attacks can have significantly more severe pain characteristics (duration, intensity, aggravation by physical activity) and accompanying symptoms (nausea, vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia) compared to migraine attacks outside the menstrual window.

Influencing natural estrogen concentrations can be a way to prevent menstrually-related migraine attacks. The aim is to reduce the hormonal concentration fluctuations and the drop in estrogen during the menstrual bleeding phase. This is based on the observation that susceptibility to migraine attacks is correlated with hormonal decline during the perimenstrual window between days -2 and +3 of menstruation [31].

There are basically two approaches available for using hormones in the preventative treatment of menstrual migraines:

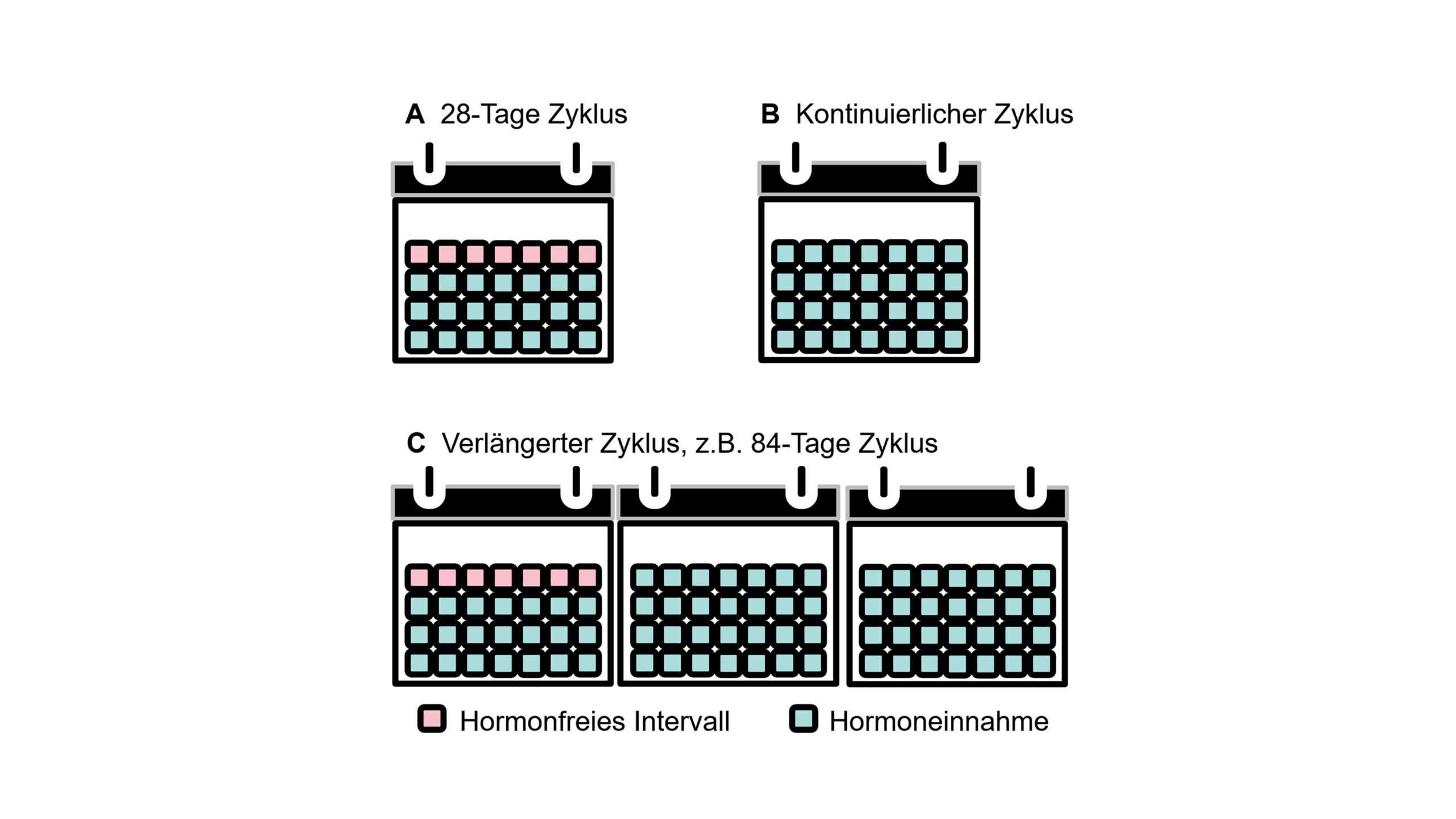

- Hormonal contraceptives can be used with different administration schedules of ethinyl estradiol depending on the duration of the hormone-free interval. Approaches include standard 21/7 regimen, variable extended regimens, and continuous regimens without hormone-free intervals (Fig. 2). Application options include oral hormonal contraceptives and vaginal rings.

- Estrogen supplements that are not designed for contraception can also be used. Examples include transdermal plasters, gel applications and subcutaneous implants. These aim to compensate for the decrease in estrogen during the perimenstrual period in menstrual-related migraines and pure menstrual migraines.

The data on the use of hormones in the prevention of menstrual migraines is very limited and sometimes contradictory. The rationale is to compensate for the decrease in endogenous estrogen in patients with pure menstrual migraine with predictable menstruation [4, 32, 33]. On the other hand, continuous administration of low doses is intended to counteract physiological hormone fluctuations. The combined administration of estrogen and gestagens is intended to stabilize hormone levels and enable contraception [4, 32, 33]. Various options for influencing the female hormonal cycle to treat migraines are described below.

Desogestrel (progestin-only drug)

The effect of desogestrel 75 µg per day in women with migraine with and without aura was examined in four open observational studies [34-37]. The study examined women who took the drug either for contraception or for medical reasons - but not for targeted migraine prophylaxis. Side effects of desogestrel use included increased headache, prolonged bleeding time, spotting and acne. In contrast, there is only limited evidence for the effectiveness of desogestrel on the course of migraine in women with migraine without aura or migraine with aura. Desogestrel may be considered in view of the favorable cardiovascular risk profile in women suffering from migraine with or without aura and additional vascular risk factors.

Combined oral contraceptives

The current study situation for the prolonged use of combined oral contraceptives in women with migraine is limited [4, 32]. Here, too, there are only open observational studies that were carried out in women who took the active ingredient for contraception or for medical reasons - not for migraine prophylaxis. Only one study used combined oral contraceptives specifically for headache prevention [38]. Available data suggest a possible benefit of long-term use of combined hormonal contraceptives in women with migraine without aura.

Desogestrel versus extended administration of combined oral contraceptives

In open-label observational studies, the effect of the desogestrel minipill was compared with prolonged administration of combined oral contraceptives in migraine without aura. In a study by Morotti et al [36] there was no difference in migraine days, headache days, headache intensity and days with triptan use. Current studies comparing the desogestrel mini-pill with combined oral contraceptives are limited. The results of the observational studies do not allow any conclusive statements to be made about effectiveness.

Combined oral contraceptives with a shortened pill-free interval

There are also only studies of low quality regarding the use of combined oral contraceptives with a shortened pill-free interval [4, 32]. These have very heterogeneous schemes. There is no evidence of the superiority of any specific regimen compared to other options. There is insufficient evidence to use the treatment solely for the prevention of migraines. In some women, the dose had to be discontinued early due to worsening migraines.

Combined oral contraceptives with oral estrogen administration during the “pill-free period”

Evidence for the use of oral combined hormonal contraceptives with oral estrogen replacement during the pill-free period is only available from a single study [39]. The current data does not allow any statements to be made about the effectiveness of this treatment regimen on the course of migraines.

Combined oral contraceptives with estradiol supplementation through a patch during the pill-free period

In a single-center study, there was no significant reduction in the number of migraine days, the severity of the migraine, and the symptoms associated with migraine [40]. Adverse events associated with transdermal estradiol supplementation included altered withdrawal bleeding. The current data does not provide sufficient justification for the use of estradiol supplementation with patches to prevent migraines during the pill-free interval.

Combined hormonal contraceptive patches

The data on the use of combined hormonal contraceptive patches is very limited. Data are only available from one study [41]. The results of this study suggest a connection between hormone withdrawal and headache occurrence. Headache days were higher during the week without patches. After removal of the patch after prolonged treatment, the frequency of headaches did not increase. The current study situation does not provide any evidence for the use of this approach.

Combined hormonal vaginal ring for contraception

The use of combined hormonal contraception with a vaginal ring on the course of migraines is also very limited [42]. The available data are not sufficient to justify its use in the prevention of migraines [4, 32].

Transdermal estradiol supplementation with gel

The effect of transdermal estradiol supplementation with gel in premenopausal patients was examined in 3 studies [43-45]. Estradiol gel 1.5 mg was used for 6 or 7 days. The effect was compared with the administration of placebo. The treatment in the study was specifically designed to prevent headaches. Serious adverse events associated with the use of estradiol gel have not been reported. Rash, anxiety, or amenorrhea have been documented as adverse events. Based on the current study situation, the use of transdermal estradiol with gel to prevent migraines cannot be sufficiently justified. On the one hand, administering transdermal estradiol with gel is easy and generally well tolerated. On the other hand, if you have irregular menstruation, the timing of application can be problematic. An increase in migraines due to delayed estrogen withdrawal can also be disadvantageous. This may be due to increased estradiol administration with additional estradiol supplementation and increased waste. The follicular increase in endogenous estrogen can also be inhibited by exogenous administration. Due to the lack of data, the administration of estrogen gel cannot currently be recommended to prevent menstrual migraines. This approach can currently be considered if all other strategies are not sufficiently effective in preventing menstrual migraines.

Transdermal estradiol supplementation through a patch

Evidence for the use of transdermal estradiol supplementation with a patch for the treatment of menstrual migraine is limited. The rationale for use is to maintain stable estradiol concentrations before bleeding begins [41]. There are currently no data proving the effectiveness of estradiol supplementation with patches on the course of migraines.

Transdermal estrogen supplementation with patch in women with pharmacologically induced menopause

The use of transdermal estradiol with a patch in women with a pharmacologically induced menopause cannot be adequately justified based on the current data. During pharmacologically induced menopause, the risk of osteoporosis, depression, hot flashes, irritability, decreased libido, and vaginal dryness is increased. This can be reduced by estrogen supplementation therapy [46]. The current study situation is not sufficient to justify its use for migraine prophylaxis.

Subcutaneous estrogen implant with cyclic progestogen

The use of a subcutaneous estrogen implant with cyclic progestogen was examined in an open observational study [47]. The data situation does not allow sufficient conclusions to be drawn for possible use to prevent migraines.

Add-back therapy

The course of headache was examined in women who received a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue, a trigger of temporary iatrogenic menopause, plus transdermal estrogen patches, alone or in combination with a progestogen (add-back therapy) [48 ]. There was a reduction in headache severity, but not headache frequency. This study provides evidence that reducing hormonal fluctuations may be useful in preventing migraines outside the menstrual window.

Phytoestrogens

Phytoestrogens are secondary plant substances such as isoflavones and lignans. They are not estrogens in the chemical sense, but have structural similarities to them. This results in a weak estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effect. The best known phytoestrogens are the isoflavones genistein, daidzein and coumestrol. Genistein and daidzein in particular are used to relieve hot flashes and other menopausal symptoms and also for menstrual migraines. An open study over 10 days in the menstrual period from -7 to +3 showed a mean reduction in headache days by 62% [49]. Half of the patients reported an absence of nausea and vomiting associated with the migraine. A randomized controlled trial confirmed the effect over 24 weeks of treatment with 60 mg soy isoflavones, 100 mg dong quai and 50 mg black cohosh [50]. There was a highly significant reduction in menstrual migraines, the use of acute medication and the severity of headaches. Phytoestrogens could therefore potentially be an option for women who do not want to take hormone treatments or cannot use them due to contraindications, such as those with a significant cardiovascular risk profile.

Further hormone treatments

Studies on the use of contraceptive options to prevent headaches have shown that the induction of amenorrhea is associated with significant headache relief [4, 32]. Therapies with progesterone-only preparations have a lower risk of cardiovascular events or complications than estrogens [4, 30, 33]. These can also be effective in preventing migraines with aura. Due to continuous intake, cycle-typical fluctuations in female sex hormones and acute estrogen withdrawal do not occur.

Testosterone shows suppression of cortical spreading depression in preclinical studies [51]. Subcutaneous administration of testosterone implants can reduce the severity of headaches in patients with androgen insufficiency. After oophorectomy with androgen insufficiency, women report an increase in migraine frequency compared to women entering natural menopause [52].

Women who undergo hormone replacement therapy during menopause experience a worsening of their headaches [53]. This is probably due to irregular release of estrogens. Hormone replacement therapy may be able to stabilize estrogen withdrawal in this situation. The lowest possible dose that can control symptoms during menopause should be chosen in order to avoid cardiovascular side effects, especially in migraine with aura. Transdermal application of estrogen or the use of continuous combined regimens such as hormone replacement therapy that avoid bleeding may be the best approach to prevent migraine in this situation.

Topiramate, menstrual migraines and contraception

Topiramate is approved for the preventative treatment of migraines and is also used for menstrual migraines. At daily doses of topiramate above 200 mg, the possibility of reduced contraceptive effectiveness and increased breakthrough bleeding should be taken into account if patients use oral contraception with combined hormonal contraceptives [54]. Women taking estrogen-containing contraceptives should be asked to report any changes in their menstrual bleeding to their doctor. Contraceptive effectiveness may be reduced by treatment with topiramate even in the absence of breakthrough bleeding [55].

CGRP mAb and menstrual migraine

There is currently no specific preventative treatment for the indication menstrual migraine. Recently, the use of monoclonal antibodies against CGRP or the CGRP receptor for the treatment of menstrual migraine has been investigated. Due to their long half-life, these have the advantage that they only need to be applied monthly or at intervals of 3 months, especially in the long term. Galcanezumab, erenumab, eptinezumab and fremanezumab are now available in Germany for the preventative treatment of migraines. In a study with erenumab [56], the course of menstrual migraine was compared in a group that responded to erenumab and in a group that did not respond to erenumab. It was found that in both groups the frequency of headaches was greater within the menstrual window than outside the menstrual window. This means that even with treatment with erenumab, migraines occur more often in the menstrual window than outside the menstrual window. Another study analyzed the effectiveness of erenumab in preventing menstrual migraines [57]. Monthly migraine days included both perimenstrual and intermenstrual migraine attacks. Erenumab 70 mg and 140 mg significantly reduced the frequency of migraine days per month compared to placebo. Data support the effectiveness of erenumab in preventing menstrual migraines [57].

Cardiovascular risk

Migraine sufferers have a risk of stroke that is approximately twice as high as healthy controls. This is especially true for migraines with aura. Migraine is as important a risk factor for stroke as thrombophilia, patent foramen ovale, arterial dissection, smoking and obesity [4, 30, 32, 33, 58-60].

Estrogens improve endothelial-dependent blood flow and lipid profiles. However, they also have prothrombotic and proinflammatory effects. These may be particularly relevant in patients who are at increased risk of stroke and other vascular events such as heart attack or deep vein thrombosis. The administration of combined oral contraceptives may in particular be associated with an earlier onset of a stroke [4, 32, 61, 62].

In principle, the presence of two independent risk factors for stroke must be carefully considered. Studies show that women who have migraine and are also taking combined hormonal contraceptives have an increased risk of stroke of 2.1-13.9 [33, 61]. The risk of stroke is correlated with the estrogen dose. Expert guidelines from the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESCRH) [32, 33], the German Society for Neurology (DGN) in collaboration with the German Migraine and Headache Society [63] and the The German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics [62] therefore does not recommend the use of combined hormonal contraceptives for patients suffering from migraines with aura. Patients with migraine without aura should not use combined hormonal contraceptives if other vascular risk factors are present. Alternatively, progestogen-only contraceptives or combined oral contraceptives with estrogen doses lower than 35 mcg may be considered.

To prevent menstrual migraines, extended cycle regimens, applications with stable hormone levels such as transvaginal administration or transdermal estradiol supplementation can be used. Low doses of estrogen may also be considered for these patients. However, the data available to date is still insufficient to make reliable statements about effectiveness and tolerability. Although progestin monotherapy has the safest vascular risk profile, side effects such as breakthrough bleeding may still be observed.

Overall, the studies show that treatment with estrogen is the treatment that is most likely to be effective and tolerable. Studies on the effectiveness and tolerability of natural estrogen will also be important in the future. A short hormone-free interval is probably most effective in preventing a drop in estrogen that could potentially trigger a migraine attack. However, further controlled studies are required in the future in order to be able to make reliable statements here.

Current guideline recommendations for the prophylaxis of menstrual migraines

The current guidelines from the German Society for Neurology (DGN) in collaboration with the German Migraine and Headache Society [63] from 2022 recommend the long-acting NSAID naproxen (half-life 12-15 h) or a triptan with a long half-life for short-term prophylaxis of menstrual migraines . The active ingredients should be given 2 days before the onset of the expected menstruation over a period of 5-6 days. Furthermore, continuous administration of a combined oral contraceptive can be considered as a preventative measure. The administration of desogestrel for prophylaxis of menstrual migraines can also be considered.

There are placebo-controlled studies on the use of frovatriptan 2.5 mg 1x, 2x or 3x per day, zolmitriptan 2.5 mg 2x or 3x per day, naratriptan 2x per day 1 mg or 2.5 mg and naproxen 2 × 550 mg per day before. The administration should take place 2 days before the expected onset of the migraine attack in the menstrual window for a total of 6-7 days. The risk of developing medication overuse headache when using naproxen or a triptan for short-term prophylaxis of menstrual migraine is considered low if otherwise little acute medication is used.

The current guidelines do not recommend percutaneous estrogen administration. The reason is a delayed onset of the migraine attack after discontinuation of the estrogen gel. Percutaneous estrogen supplementation should only be considered if other preventative measures are not effective. The prerequisite for this procedure is a regular cycle to determine the time of application. Additional percutaneous estrogen supplementation in the pill-free interval is not recommended for migraine prophylaxis of menstrual migraines due to a lack of data.

According to the current guidelines, continuous administration of a combined oral contraceptive can be considered as a preventative measure. The aim is to reduce the number of cycles and the migraine attacks they trigger. Continuous use for up to 2 years is considered safe. The guideline points out that this preventative treatment of headaches and migraine attacks outside the menstrual window has so far only been examined in open, uncontrolled studies. Since combined oral contraceptives can significantly increase the risk of a stroke and migraine with aura itself is a risk factor for strokes, the cardiovascular risk profile of each patient must be taken into account individually. According to the guideline, the continuous use of combined oral contraceptives is of least concern in patients with only migraine without aura and without other cardiovascular risk factors. Otherwise, the indication must be strictly defined, the patient must be informed accordingly and the procedure must be decided on a case-by-case basis. Combined oral contraceptives with a low estrogen content should generally be preferred. A contraindication to the administration of combined oral contraceptives is highly active migraine with aura in patients with an increased vascular risk profile.

Adequate contraception must also be ensured with various preventative therapies for migraines. This applies in particular to treatment with monoclonal antibodies against CGRP or the CGRP receptor, botulinum toxin, flunarizine, topiramate and valproate.

Hormonal contraceptives, stroke risk and migraines in practice

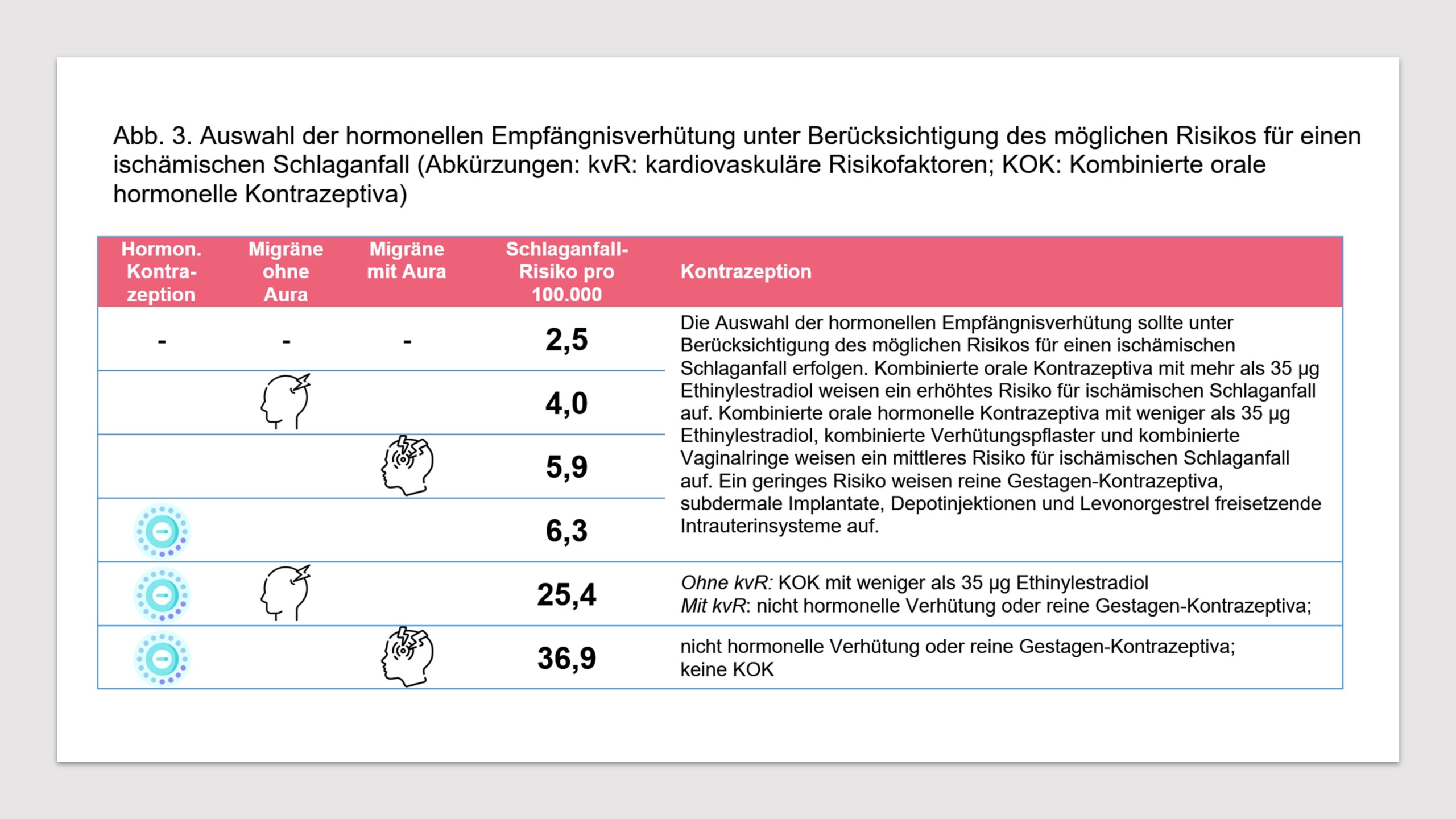

Migraine is a risk factor for stroke and other vascular events. There is extensive evidence that an increased risk of ischemic stroke is associated with both migraine without aura and migraine with aura [4, 30, 32, 33, 58-60]. Since the risk of stroke can also be increased when using combined hormonal contraceptives [4, 32, 61], the relevant question is whether the simultaneous existence of a migraine and the use of combined hormonal contraceptives can further increase the risk of stroke. The European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESCRH) analyze this question in a consensus statement [33]. The absolute risk of ischemic stroke in women not using hormonal contraception is 2.5/100,000 per year. The same risk for women using hormonal contraceptives is 6.3/100,000. If women suffer from migraine with aura, the risk of an ischemic stroke without taking hormonal contraceptives is 5.9/100,000 per year. The risk of an ischemic stroke if you have migraines with aura and use hormonal contraceptives is 36.9/100,000 per year. Looking at women who suffer from migraine without aura, the risk of ischemic stroke is 4.0/100,000 per year. If hormonal contraceptives are used in this group, the risk is 25.4/100,000 per year (see Fig. 3).

The European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESCRH) derive the following expert consensus from the data [33]:

- If women want to use hormonal contraception, a clinical examination is recommended to analyze whether they have migraine with or without aura. In addition, migraine frequency (headache days per month) and vascular risk factors should be determined before prescribing combined hormonal contraceptives.

- Women who want to use hormonal contraception are recommended to use a special tool to diagnose migraine and its subtypes. Questionnaires or digital options such as the migraine app (can be downloaded free of charge from the app stores under this name) can be used for this purpose.

- The choice of hormonal contraception should be made taking into account the possible risk of ischemic stroke. Combined oral contraceptives containing more than 35 mcg ethinyl estradiol have an increased risk of ischemic stroke. Combined oral hormonal contraceptives containing less than 35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol, combined contraceptive patches, and combined vaginal rings have an intermediate risk of ischemic stroke. Progestin-only contraceptives, subdermal implants, depot injections and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems pose a low risk.

- Women who have migraine with aura and are seeking hormonal contraception are advised not to prescribe combined hormonal contraceptives.

- For women suffering from migraine with aura and seeking contraception, non-hormonal contraceptive methods (condoms, copper-containing intrauterine devices, or progestogen-only contraceptives) are recommended as the preferred option. If migraine with aura occurs and combined hormonal contraceptives are already being used for contraception, a switch to non-hormonal contraceptives or progestin-only contraceptives is recommended.

- In women who suffer from migraines without aura and who want to use hormonal contraception, but who have additional risk factors (smoking, arterial hypertension, obesity, cardiovascular disease, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in the past), non-hormonal contraception or progestogen-only contraceptives are used recommended as a preferred option.

- In women who suffer from migraine without aura and use hormonal contraceptives and have no additional risk factors, the use of combined hormonal contraceptives with a dose of less than 35 mcg ethinyl estradiol for contraception is recommended. At the same time, the frequency and characteristics of migraines should be monitored.

- If women suffer from migraine with aura or migraine without aura and who require hormonal treatment due to polycystic ovary syndrome or endometriosis, it is recommended that hormonal treatment with pure progestin or combined hormonal contraceptives be used according to clinical considerations.

- If women are starting contraception with combined hormonal contraceptives and develop a new migraine with aura or in whom a migraine without aura occurs for the first time in close proximity to the start of taking the hormonal contraceptive, a switch to non-hormonal contraceptives or progestin-only is recommended -Contraceptives recommended.

- If women suffering from migraines with or without aura require emergency contraception, the use of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg orally, ulipristal acetate 30 mg orally or a copper-containing intrauterine device is recommended.

- If women with migraine with or without aura start taking hormonal contraception, specific tests such as thrombophilia screening, patent foramen ovale examination or imaging tests are not relevant for the decision to use hormonal contraception unless the medical history or the Findings require appropriate investigations due to specific information.

- For women with non-migraine headaches who are seeking hormonal contraception, any low-dose hormonal contraceptive can be used.

Overall, evidence on the association between ischemic stroke and the use of hormonal contraceptives is limited. Essentially only uncontrolled observational studies are available. Further studies need to be conducted in the future to further determine the possible risk of hormonal contraceptives in women with migraines. Nevertheless, data to date show an increased risk of ischemic stroke associated with the use of hormonal contraceptives in women with migraine. In this situation it is necessary that special attention is paid to safety aspects during use. Although the risk of a stroke is not very high, a stroke can have catastrophic consequences for individuals and their families. For these reasons, alternative contraception should be used if there is a corresponding increased risk.

literature

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS), The International Classification of Headache Disorders ICHD-3, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia, 2018. 38 (1): p. 1-211.

- Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Cephalalgia, 1988. 8 Suppl 7 : p. 1-96.

- The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia, 2004. 24 Suppl 1 : p. 9-160.

- Nappi, RE, et al., Role of Estrogens in Menstrual Migraine. Cells, 2022. 11 (8).

- Russell, MB, Genetics of menstrual migraine: the epidemiological evidence. Curr Pain Headache Rep, 2010. 14 (5): p. 385-8.

- Somerville, BW, The role of estradiol withdrawal in the etiology of menstrual migraine. Neurology, 1972. 22 (4): p. 355-65.

- Pavlović, JM, et al., Sex hormones in women with and without migraine. Neurology, 2016. 87 (1): p. 49.

- Cornil, CA, GF Ball, and J. Balthazart, Functional significance of the rapid regulation of brain estrogen action: where do the estrogens come from? Brain Res, 2006. 1126 (1): p. 2-26.

- Boese, AC, et al., Sex differences in vascular physiology and pathophysiology: estrogen and androgen signaling in health and disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2017. 313 (3): p. H524-h545.

- Rodriguez-Acevedo, AJ, et al., Genetic association and gene expression studies suggest that genetic variants in the SYNE1 and TNF genes are related to menstrual migraine. J Headache Pain, 2014. 15 (1): p. 62.

- Vetvik, KG and EA MacGregor, Menstrual migraine: a distinct disorder needing greater recognition. Lancet Neurol, 2021. 20 (4): p. 304-315.

- Shughrue, PJ and I. Merchenthaler, Estrogen is more than just a “sex hormone”: novel sites for estrogen action in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. Front Neuroendocrinol, 2000. 21 (1): p. 95-101.

- Facchinetti, F., et al., Neuroendocrine evaluation of central opiate activity in primary headache disorders. Pain, 1988. 34 (1): p. 29-33.

- Tassorelli, C., et al., Changes in nociceptive flexion reflex threshold across the menstrual cycle in healthy women. Psychosom Med, 2002. 64 (4): p. 621-6.

- Krause, DN, et al., Hormonal influences in migraine – interactions of estrogen, oxytocin and CGRP. Nat Rev Neurol, 2021. 17 (10): p. 621-633.

- De Icco, R., et al., Modulation of nociceptive threshold by combined hormonal contraceptives in women with estrogen-withdrawal migraine attacks: a pilot study. J Headache Pain, 2016. 17 (1): p. 70.

- Warfvinge, K., et al., Estrogen receptors α, β and GPER in the CNS and trigeminal system – molecular and functional aspects. J Headache Pain, 2020. 21 (1): p. 131.

- Kitazawa, T., et al., Non-genomic mechanism of 17 beta-oestradiol-induced inhibition of contraction in mammalian vascular smooth muscle. J Physiol, 1997. 499 (Pt 2) (Pt 2): p. 497-511.

- Somjen, GG, Mechanisms of spreading depression and hypoxic spreading depression-like depolarization. Physiol Rev, 2001. 81 (3): p. 1065-96.

- Edvinsson, L., et al., CGRP as the target of new migraine therapies – successful translation from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Neurol, 2018. 14 (6): p. 338-350.

- Knight, YE, L. Edvinsson, and PJ Goadsby, 4991W93 inhibits release of calcitonin gene-related peptide in the cat but only at doses with 5HT(1B/1D) receptor agonist activity? Neuropharmacology, 2001. 40 (4): p. 520-5.

- Ashina, M., Migraine. N Engl J Med, 2020. 383 (19): p. 1866-1876.

- Forbes, RB, M. McCarron, and CR Cardwell, Efficacy and Contextual (Placebo) Effects of CGRP Antibodies for Migraine: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Headache, 2020. 60 (8): p. 1542-1557.

- Drellia, K., et al., Anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies for migraine prevention: A systematic review and likelihood to help or harm analysis. Cephalalgia, 2021. 41 (7): p. 851-864.

- Valdemarsson, S., et al., Hormonal influence on calcitonin gene-related peptide in man: effects of sex difference and contraceptive pills. Scand J Clin Lab Invest, 1990. 50 (4): p. 385-8.

- Gupta, P., et al., Effects of menopausal status on circulating calcitonin gene-related peptide and adipokines: implications for insulin resistance and cardiovascular risks. Climacteric, 2008. 11 (5): p. 364-72.

- Aggarwal, M., V. Puri, and S. Puri, Effects of estrogen on the serotonergic system and calcitonin gene-related peptide in trigeminal ganglia of rats. Ann Neurosci, 2012. 19 (4): p. 151-7.

- Cetinkaya, A., et al., Effects of estrogen and progesterone on the neurogenic inflammatory neuropeptides: implications for gender differences in migraine. Exp Brain Res, 2020. 238 (11): p. 2625-2639.

- Yamanaka, G., et al., Role of Neuroinflammation and Blood-Brain Barrier Permutability on Migraine. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22 (16).

- Cupini, LM, I. Corbelli, and P. Sarchelli, Menstrual migraine: what it is and does it matter? J Neurol, 2021. 268 (7): p. 2355-2363.

- MacGregor, EA, et al., Incidence of migraine relative to menstrual cycle phases of rising and falling estrogen. Neurology, 2006. 67 (12): p. 2154-8.

- Sacco, S., et al., Effect of exogenous estrogens and progestogens on the course of migraine during reproductive age: a consensus statement by the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESCRH). J Headache Pain, 2018. 19 (1): p. 76.

- Sacco, S., et al., Hormonal contraceptives and risk of ischemic stroke in women with migraine: a consensus statement from the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESC). J Headache Pain, 2017. 18 (1): p. 108.

- Merki-Feld, GS, et al., Improvement of migraine with change from combined hormonal contraceptives to progestin-only contraception with desogestrel: How strong is the effect of taking women off combined contraceptives? J Obstet Gynaecol, 2017. 37 (3): p. 338-341.

- Morotti, M., et al., Progestogen-only contraceptive pill compared with combined oral contraceptive in the treatment of pain symptoms caused by endometriosis in patients with migraine without aura. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2014. 179 : p. 63-8.

- Morotti, M., et al., Progestin-only contraception compared with extended combined oral contraceptive in women with migraine without aura: a retrospective pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2014. 183 : p. 178-82.

- Nappi, RE, et al., Effects of an estrogen-free, desogestrel-containing oral contraceptive in women with migraine with aura: a prospective diary-based pilot study. Contraception, 2011. 83 (3): p. 223-8.

- Coffee, AL, et al., Extended cycle combined oral contraceptives and prophylactic frovatriptan during the hormone-free interval in women with menstrual-related migraines. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2014. 23 (4): p. 310-7.

- Calhoun, AH, A novel specific prophylaxis for menstrual-associated migraine. South Med J, 2004. 97 (9): p. 819-22.

- Macgregor, EA and A. Hackshaw, Prevention of migraine in the pill-free interval of combined oral contraceptives: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study using natural estrogen supplements. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care, 2002. 28 (1): p. 27-31.

- LaGuardia, KD, et al., Suppression of estrogen-withdrawal headache with extended transdermal contraception. Fertil Steril, 2005. 83 (6): p. 1875-7.

- Calhoun, A., S. Ford, and A. Pruitt, The influence of extended-cycle vaginal ring contraception on migraine aura: a retrospective case series. Headache, 2012. 52 (8): p. 1246-53.

- de Lignières, B., et al., Prevention of menstrual migraine by percutaneous oestradiol. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed), 1986. 293 (6561): p. 1540.

- Dennerstein, L., et al., Menstrual migraine: a double-blind trial of percutaneous estradiol. Gynecol Endocrinol, 1988. 2 (2): p. 113-20.

- MacGregor, EA, et al., Prevention of menstrual attacks of migraine: a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Neurology, 2006. 67 (12): p. 2159-63.

- Martin, V., et al., Medical oophorectomy with and without estrogen add-back therapy in the prevention of migraine headache. Headache, 2003. 43 (4): p. 309-21.

- Magos, AL, KJ Zilkha, and JW Studd, Treatment of menstrual migraine by oestradiol implants. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 1983. 46 (11): p. 1044-6.

- Murray, SC and KN Muse, Effective treatment of severe menstrual migraine headaches with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and “add-back” therapy. Fertil Steril, 1997. 67 (2): p. 390-3.

- Ferrante, F., et al., Phyto-oestrogens in the prophylaxis of menstrual migraine. Clin Neuropharmacol, 2004. 27 (3): p. 137-40.

- Burke, BE, RD Olson, and BJ Cusack, Randomized, controlled trial of phytoestrogen in the prophylactic treatment of menstrual migraine. Biomed Pharmacother, 2002. 56 (6): p. 283-8.

- Eikermann-Haerter, K., et al., Androgenic suppression of spreading depression in familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 mutant mice. Ann Neurol, 2009. 66 (4): p. 564-8.

- Nappi, RE, K. Wawra, and S. Schmitt, Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2006. 22 (6): p. 318-23.

- MacGregor, EA, Menstrual and perimenopausal migraine: A narrative review. Maturitas, 2020. 142 : p. 24-30.

- Schoretsanitis, G., et al., Drug-drug interactions between psychotropic medications and oral contraceptives. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol, 2022. 18 (6): p. 395-411.

- Lazorwitz, A., et al., Effect of Topiramate on Serum Etonogestrel Concentrations Among Contraceptive Implant Users. Obstet Gynecol, 2022. 139 (4): p. 579-587.

- Ornello, R., et al., Menstrual Headache in Women with Chronic Migraine Treated with Erenumab: An Observational Case Series. Brain Sci, 2021. 11 (3).

- Pavlovic, JM, et al., Efficacy and safety of erenumab in women with a history of menstrual migraine. J Headache Pain, 2020. 21 (1): p. 95.

- Adewuyi, EO, et al., Shared Molecular Genetic Mechanisms Underlie Endometriosis and Migraine Comorbidity. Genes (Basel), 2020. 11 (3).

- Saddik, SE, et al., Risk of Stroke in Migrainous Women, a Hidden Association: A Systematic Review. Cureus, 2022. 14 (7): p. e27103.

- Siao, WZ, et al., Risk of peripheral artery disease and stroke in migraineurs with or without aura: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Int J Med Sci, 2022. 19 (7): p. 1163-1172.

- Champaloux, SW, et al., Use of combined hormonal contraceptives among women with migraines and risk of ischemic stroke. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2017. 216 (5): p. 489.e1-489.e7.

- Hormonal Contraception Guideline of the DGGG, SGGG and OEGGG (S3 level, AWMF Registry No. 015/015, November 2019). https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/015-015 .

- Diener, H.-C., et al., Therapy of migraine attacks and prophylaxis of migraine, S1 guidelines, 2022, DGN and DMKG , in guidelines for diagnostics and therapy in neurology , DGfN (ed.), editor. 2022: Online: www.dgn.org/leitlinien .

PDF download publication Pain Medicine 02 2023

Leave a comment