Note : The following explanations describe scientific theories on the development of cluster headaches. They are written in scientific terminology.

Site of cluster headache origin

One of the key characteristics of cluster headaches is their location behind and around the eye . Cluster headaches can also occur in people who the eyeball on the same side as the headache removed unlikely pain within the eye itself . For this reason, it is probable that the headache originates in structures around or behind the eye . When determining which structures play a crucial role in the development of cluster headaches, it is important to note that cluster headaches can also occur in other symptomatic diseases . Examples of such defined clinical entities include upper cervical meningiomas , parasellar meningiomas , large arteriovenous malformations in various ipsilateral brain structures , ethmoid cysts in the region of the clivus and suprasellar cisterns , pituitary adenomas , calcifications in the region of the third ventricle, ipsilateral aneurysms, and aneurysms of the anterior communicating artery . All these structures show a relationship to the midline in the region of the cavernous sinus . It is therefore reasonable to assume that the cavernous sinus is the anatomical structure that is particularly relevant to the genesis of cluster headaches.

during the spontaneous course of a cluster headache. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans performed during a cluster headache attack showed increased contrast enhancement in the region of the cavernous sinus . This indicates an inflammatory process occurring in the cavernous sinus during the attack. Furthermore, evidence of inflammatory changes was detected in the cerebrospinal fluid and peripheral blood during the cluster headache episode . Phlebography revealed evidence of venous vasculitis in the region of the cavernous sinus and the superior ocular vein during the cluster period. Interestingly, these abnormal findings completely regressed during remission . These investigations suggest that the venous system and the cavernous sinus play a significant role in the development of cluster headache pain.

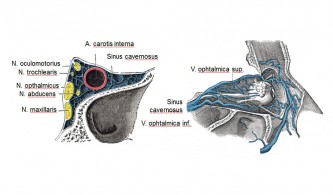

The parasympathetic innervation is provided by the deep petrosal nerve and the orbital branches from the sphenopalatine ganglion , as well as other microganglia. The parasympathetic fibers pass through the supraorbital fissure in the region of the cavernous sinus . The sensory fibers supplying the orbit are provided by the ophthalmic nerve and also partially pass through the region of the cavernous sinus . Some of these fibers supply the basilar artery and, for this purpose, run alongside the abducens nerve for a portion of their course. The greater superficial petrosal nerve also supplies the internal carotid artery with sensory fibers. The cavernous sinus is innervated by fibers of the trigeminal and facial nerves . The dural veins and dural sinuses are innervated by nociceptive fibers from the tentorial nerve . The sensory, sympathetic, and parasympathetic fibers form a plexus in the region of the cavernous sinus . Additional mechanoreceptors are located along the course of the internal carotid artery in the carotid canal.

The origin of cluster headaches can be localized the cavernous sinus based on the anatomical structures and the aforementioned findings Carotid angiography reveals dilatation , or obstruction of passage in orbital phlebography during cluster periods. These changes, particularly the dilatation of the cavernous sinus, are observed ipsilateral to the side of the cluster headache. Additionally, vascular dilatations can be observed during attacks in the ophthalmic artery , the anterior cerebral artery , and the middle cerebral artery

Vascular dilation in the ophthalmic and anterior cerebral arteries also been between cluster headache attacks . Because of this, it remains unclear whether the vascular dilation directly related to the development of the pain . Regardless of causality, however, the ipsilateral nature of the dilation suggests a connection between phases of dilation and the headache episodes.

Phlebographic examinations reveal evidence of phlebitis in the region of the superior ophthalmic vein and the cavernous sinus similar findings also observed in Tolosa-Hunt syndrome , in which granulomatous inflammation in the corresponding structures is assumed. Both conditions can be treated very effectively with anti -inflammatory corticosteroid therapy . It remains completely unclear why inflammation of the cavernous sinus and surrounding veins occurs during a cluster headache episode.

Hypothetically , it can be assumed that the frequently described narrowing of the airways in the nasal and sinus region in patients with cluster headaches could lead to impaired ventilation of the ethmoid cells , thus promoting a corresponding ipsilateral infection. The subsequent spread of inflammation to the ipsilateral cavernous sinus is a possible hypothesis for the pathogenesis of cluster headaches. However, there is currently no evidence to support this. These considerations are reinforced by the increased incidence in smokers. Furthermore, active cluster periods typically occur during seasons with a higher susceptibility to upper respiratory tract infections.

Neuroimaging and morphometric studies

Pathophysiological considerations regarding the development of cluster headaches must take into account the timing of onset, the temporary clustering of attacks, the location of the headaches, and the involvement of sympathetic and parasympathetic activation. Originally, the development of cluster headaches was explained by changes in vascular diameter. This also helped to clarify the effects of vasoconstrictive substances and the triggering by vasodilators such as nitroglycerin and histamine.

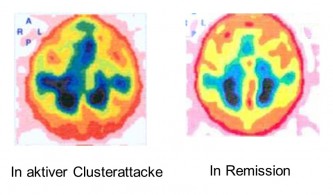

Positron emission tomography (PET) can be used to examine changes in regional cerebral blood flow. High-resolution PET scans allow even subtle changes in regional cerebral blood flow to be detected at rest and during certain brain activation processes. Cluster headache attacks can be experimentally induced with nitroglycerin. These experimentally triggered attacks do not differ from spontaneously occurring cluster headache attacks with respect to essential pathophysiological parameters. Experimentally induced cluster headaches, like spontaneously occurring cluster headaches, can be effectively treated with sumatriptan.

The research group of May et al. (1998) described a significant activation in the ipsilateral hypothalamus during acute cluster headaches in a patient group with cluster headaches, compared to the headache-free period.

- No brainstem activation was found in cluster headache patients, so a distinction from possible pathophysiological brainstem processes such as in migraine was assumed.

- These findings also support clinical experience that the drugs used to treat cluster headaches are not effective in preventing migraines, and vice versa.

- no brainstem activation could be detected during experimental pain stimulation of the forehead with capsaicin , nor was any hypothalamic activation by experimental pain induction with capsaicin in the forehead area.

- Based on these findings, it was concluded that hypothalamic activation is a specific process for cluster headache, associated with pain initiation or maintenance, and not a secondary response of nociceptor activation in the area of the first trigeminal branch.

- The hypothalamus is to be brought into a state of heightened activation during the acute cluster headache period. Circadian rhythms and sleep-wake cycles are intended to activate the hypothalamic nuclei as the primary driving force.

The concept of primary headaches assumes that functional changes underlie the headaches. Structural changes in the brain are not assumed in primary headaches. However, using voxel-based morphometry, a significant structural change in gray matter density has been described compared to healthy controls. These changes were found both during and outside of the active cluster period. The differences were localized bilaterally in the diencephalon region adjacent to the third ventricle and rostral to the aqueduct. This region coincides with the area of the inferior posterior hypothalamus . Corresponding findings are not observed in migraine patients. This has led to the hypothesis that structural changes may be associated with the disease process in cluster headaches, whereas purely functional mechanisms play a role in migraine.

Based on imaging findings from PET and fMRI studies with voxel-based morphometric analyses, direct vasoconstrictive and dilatoric vascular changes have moved away from the primary focus of the pathophysiology of cluster headaches. Functional and structural changes in the midbrain and pons have been postulated in migraine, while corresponding changes in the hypothalamic gray matter have been suspected in cluster headaches. In addition to functional activation mechanisms, structural changes in the density of gray matter in the hypothalamus are also being discussed.

Based on these findings, deep brain stimulation (DBS) was proposed for the treatment of cluster headaches. The target area for DBS was selected based on morphometric studies. The first procedures were performed by the Italian research group of Leone et al. in 2000. However, due to disappointing long-term results and significant risks, including fatal ones (implantation-induced lethal intracerebral hemorrhage), DBS for cluster headaches has remained an experimental therapy and has largely been abandoned. The only placebo-controlled, double-blind study to date found no significant difference between actual and sham stimulation (Fontaine et al., 2010). As a rule, further preventive medication is necessary despite DBS. Intensive long-term monitoring, medication adjustment, and the natural course of the condition are all confounded with the treatment outcomes. Insufficient treatment efficacy is sometimes attributed to incorrect electrode placement during DBS.

It remains unclear whether the structural changes in the inferior posterior hypothalamus correlate with the pain in the sense of nonspecific activation, are a consequence of previous therapy, or are the cause of the headaches. The application of deep brain stimulation for cluster headaches remains experimental, and we see no place for it in clinical care. The work by Leone et al. (2001) is considered the only example of the therapeutic application of imaging findings, but it has not proven effective. In our view, the studies did not justify clinical use.

Stimulation of target areas and occasional improvement should not lead to the assumption that these regions are causally crucial for the pathophysiology of cluster headaches. Stimulation of neural structures in both the central and peripheral nervous systems can modulate numerous pain mechanisms and have a non-specific effect on the pain process. This is also supported by the improvement rates of cluster headaches and other pain syndromes following stimulation of the greater occipital nerve or the sphenoid ganglion. Drawing conclusions about the cause of cluster headaches based solely on stimulation results does not appear to be sufficiently justified at present. The hypothetical role of the inferior posterior hypothalamus in cluster headaches is shown in the adjacent figure (abbreviations: GCRP calcitonin gene-related peptide, SPG sphenopalatine ganglion, SSN superior salivatory nucleus, VIP vasoactive intestinal polypeptide).

Recent studies have analyzed the long-term course of cluster headaches and changes in gray matter. Nägel et al. (2011) examined 75 cluster headache patients (22 episodically during the active period, 35 episodically outside the active period, and 18 chronically cluster headache patients) and compared gray matter changes in 61 healthy, matched controls using voxel-based morphometry (VBM). Patients with recent acute cluster headache attacks during the active period showed the most pronounced reductions in gray matter within the central pain-processing system. In chronically cluster headache patients, additional changes were detected in the anterior cingulate cortex, the amygdala, and the secondary somatosensory cortex. Outside the active period, no changes were observed in these areas in patients with episodic cluster headache. No changes in the hypothalamus were found in either the subgroups or the overall group. These data demonstrate a loss of gray matter in the central pain-processing systems, particularly in patients with chronic cluster headache. In contrast, no changes were found in the hypothalamus. The findings are similar to those of patients with other pain disorders. They support the assumption that the morphological changes are effects of acute pain and not the primary cause. The changes may be correlates of the chronicity processes. This is supported by the particularly pronounced abnormalities in patients with chronic cluster headache. Changes in the hypothalamus were not detected, so the role of the hypothalamus in the development of cluster headache remains controversial (Nägel et al. 2011; Holle and Obermann 2011).

Inflammation in the cavernous sinus

Orbital phlebograms performed on cluster headache patients during active cluster periods revealed evidence of inflammatory processes in the cavernous sinus and the superior ophthalmic vein of unclear origin. Within the cavernous sinus, sensory fibers of the ophthalmic nerve, sympathetic fibers supplying the ipsilateral eyelid, eye, face, orbit, and retro-orbital vessels, venous vessels draining the orbit and face, and the internal carotid artery are bundled together in a very confined, bony space (see figure). Local inflammatory processes can thus affect both sensory and autonomic nerve fibers as well as venous and arterial vessels. Irritation of the nerve fibers is conceivable both directly by inflammatory neuropeptides and as a consequence of mechanical compression by inflamed and swollen vessels. This theory can explain cluster pain and its diverse accompanying symptoms. The ability of vasodilating substances to provoke cluster attacks during active cluster periods (alcohol, nitroglycerin, histamine, hypoxia) and of vasoconstrictive substances (oxygen, sumatriptan, ergotamine) to quickly terminate them is also compatible with the model.

It is assumed that a basal inflammatory response is present during active cluster periods, which exacerbates in attacks. The orbital phlebograms, which suggested an inflammatory process, were performed between attacks during a cluster period. In patients with chronic or episodic cluster headaches, Tc-99m albumin SPECT was performed 10 minutes, 1 hour, 3 hours, and 6 hours after injection of 600 MBq Tc-99m human serum albumin (HSA) during an active cluster period. In the healthy control group, an inhomogeneous distribution of activity was found. In contrast, in the cluster headache patients, tracer accumulation was found in the region of the cavernous sinus, sphenoparietal sinus, ophthalmic vein, petrosal sinus, and sigmoid sinus during the active phase (see figure). The side of the cluster headache and the regional protein extravasation corresponded in all cluster headache patients. After effective prophylactic treatment with verapamil or corticosteroids, the increased tracer uptake disappeared. An active cluster headache period is thus associated with regional plasma protein extravasation in venous sinuses at the base of the brain as a sign of local vascular inflammation. Successful treatment with verapamil or corticosteroids blocks both ipsilateral plasma extravasation and cluster headache attacks. In chronic cluster headache, this underlying inflammatory reaction is continuously present, while in the episodic form it is only periodic. This also explains the high and reliable efficacy of anti-inflammatory corticosteroids for the prophylaxis of cluster headaches. The cavernous sinus is traversed by the carotid artery, the optic nerves, the ophthalmic nerves, and the facial nerve. All of these nerves are affected during a cluster attack. This theory explains cluster pain and its diverse accompanying symptoms. The ability of vasodilating substances to provoke cluster attacks during active cluster periods (alcohol, nitroglycerin, histamine, hypoxia) and of vasoconstrictive substances (oxygen, sumatriptan, ergotamine) to quickly terminate them is also compatible with the model.

The adjacent image shows the diagnostic evidence of unilateral plasma extravasation as an expression of vasculitis in the cavernous sinus in a patient with an active cluster period. On the side of the cluster attacks in the right cavernous sinus and superior petrosal sinus, clear signs of inflammation are found in the form of asymmetric plasma leakage from the veins in Tc-99m albumin SPECT scans at 10 minutes, 1 hour, 3 hours, and 6 hours after injection of 600 MBq of Tc-99m human serum albumin (HSA). While an initial symmetry of the venous vascular system is observed after 10 minutes, a marked asymmetry is evident after three hours due to the increasing plasma extravasation over time. These changes are not observed during the remission phase

The onset of pain during sleep, the patient's upright sitting in bed or getting up, and their motor restlessness also become understandable: Venous drainage of the cavernous sinus is less efficient when lying down due to hydrostatic conditions than when sitting or standing. It can therefore be assumed that an underlying inflammatory response is present during active cluster periods, which exacerbates in attacks. This also explains why smoking and seasonal transitions, with their increased susceptibility to sinus infections, are associated with a higher probability of active cluster periods.

Anti-inflammatory medications such as cortisone lead to the rapid cessation of active cluster headache periods. However, due to long-term side effects, they are not suitable for long-term therapy. Calcium channel blockers, such as verapamil, prevent the inflammatory effects by preventing plasma extravasation and are suitable for long-term treatment. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as indomethacin can be particularly effective in specific forms of cluster headache, such as chronic paroxysmal hemicrania, but are usually insufficient for cluster headaches. This also applies to aspirin, ibuprofen, etc. These medications are ineffective during an acute attack, yet many people take them and mistakenly believe that the subsiding of attacks after 2-3 hours is due to these medications. There are also case reports on the effectiveness of warfarin (Coumadin) in cluster headache attacks; this medication likely prevents the intensification of platelet aggregation in the cavernous sinus caused by venous vasculitis. The effectiveness of azothioprine in case reports could be based on a reduction of the underlying inflammatory response.

Neuronal changes

Various electrophysiological methods have been used to analyze changes in neuronal activity during cluster headaches. Here, too, side-by-side analysis and analysis during the cluster period compared to the remission period are useful. Evidence of disruption in sensory pathways can be obtained through the use of auditory brainstem evoked potentials and somatosensory evoked potentials.

Pupillary reactions in cluster headache patients were analyzed in particular detail Miosis is one of the most striking characteristics of cluster headache. The consensual pupillary light reflex observed more quickly and pronounced in cluster headache patients dysregulation on the affected side than in the remission phase. The pupillary response to painful electrical stimuli of the sural nerve reduced on the side affected by cluster headache . This reduced pupillary dilation may be caused by an increased supply of released neuropeptides such as substance P and neurokinin A, which lead to direct pupillary constriction. Direct electrical stimulation of the infratrochlear nerve also results in unilateral pupillary constriction , which is not mediated by cholinergic mechanisms. This reaction can also be mediated by the release of substance P and neurokinin A. These neuropeptides may be released in increased amounts during cluster attacks (see above), as the response to stimulation of the infratrochlear nerve significantly weaker . These findings suggest that not only sympathetic pathways but also sensory fibers of the trigeminal nerve may play a significant role in the pathophysiology of cluster headaches. Further evidence for altered sensory properties is the increased pain sensitivity observed in cluster headache patients during headache-free periods, which is particularly pronounced on the side affected by the headache. During remission, pain sensitivity returns to normal. In conjunction with the increased response to stimulation of the infratrochlear nerve, these findings can be interpreted indication of increased excitability of nociceptive neurons of the trigeminal nerve

Further changes in pupillary response are also observed with pharmacological stimulation , bilateral instillation of indirect sympathomimetics such as hydroxyamphetamine results reduced mydriasis on the side affected during the active cluster phase outside of an attack. Conversely, administration of a direct sympathomimetic such as phenylephrine to the eye affected by cluster headache leads to increased mydriasis . These findings suggest reduced sympathetic function on the symptomatic side . Experimentally induced sweating, for example, with the application of heat, is also reduced on the symptomatic side in affected patients during the active phase in headache-free periods. In contrast, administration of pilocarpine results in increased sweating on the symptomatic side. These findings can also be interpreted sympathetic fiber dysfunction The reduced activity leads to hypersensitivity of the postsynaptic receptors. However, the localization of sympathetic hyperfunction is not necessarily peripheral , as similar findings can also be observed in central Horner 's syndrome